ARGONAUTICA AND BIBLE

|

The Golden Fleece has frequently been compared to the ram sacrifice substituted for Isaac in Genesis 22:9-18, as detailed on my page about the Golden Fleece as a divine covenant. Similarly, some have thought that the ship Argo was in fact a garbled recollection of Noah's Ark.

But these are hardly the only places where the Argonaut myth has been thought to cross paths with the Bible. In the field of "alternative" history, there is no end to such comparisons. The Russian Anatoly Fomenko, who believes that the Middle Ages were a British invention designed to deny Russia her true glory, believes the Argonauts' story was a virtually scene-by-scene replay of the Bible, including elements of Exodus and Genesis, and much more: The legends [of the Argonauts] resemble the accounts of wars and campaigns of both Joshua and Alexander the Great to a great extent. The myth of the Argonauts might be yet another duplicate of medieval chronicles describing the wars of the [12th to 14th] centuries [...] Source: Anatoly T. Fomenko, History: Fiction or Science? vol. 2 (Paris: Delamere, 2005), 342. Fomenko also thinks Jason, Medea, and the snake parallel Adam, Eve, and the serpent, a suggestion made long before by Edward Burnaby-Greene in his 1780 translation of the Argonautica of Apollonius. Greene thought the lovers' escape from Colchis paralleled the expulsion from Eden in Milton's Paradise Lost (p. 147). |

Jason and Jesus

The most persistent link between the Argonauts and the Bible has been the repeated assertion that Jason was somehow a Greek corruption or premonition of Jesus, a theme that appeared repeatedly in the Middle Ages and continues down to the present day among "alternative" historians and New Age mystics. The connection derives from a quirk of language whereby the Hebrew name Joshua (Yeshua), was transliterated into to Greek as both Jesus (Iesus) and Jason (Iason).

JASON (’Ιάσων, he that will cure, originally the name of the leader of the Argonauts), a Common Greek name, which was frequently adopted by Hellenizing Jews as the equivalent of Jesus, Joshua (’Ιησούς; comp. Josephus, Ant. xii, 5,1; Aristeas, Hist. apud Hody, p. 7), probably with some reference to its supposed connection with ιάσϑαι (i. e. the healer). A parallel change occurs in Alcimus (Eliakim), while Nicolaus, Dositheus, Menelaus, etc, were direct translations of Hebrew names. It occurs with reference to several men in the Apocrypha, and one in the New Testament.

Source: John McClintock and James Strong, Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological and Ecclesiastical Literature, vol. 4 (New York Harper & Bros., 1872), s.v. "Jason."

The German scholar Arthur Drews took this still further, arguing that Jason was the inspiration for the myth of Jesus:

The name [Jesus/Joshua] was fairly common among the Jews, and in this connection it is equivalent among the Hellenistic Jews to the name Jason or Jasios, which again is merely a Greek version of Jesus. […] Here again the idea of healing and saving is combined in the name, and would easily lead to the giving of the name to the saviour of the Jewish mystery-cult. Epiphanius clearly perceived this connection when he translated the name Jesus "healer" or "physician" (curator, therapeutes). It is certain that this allusion to the healing activity of the servant of God and his affinity with the widely known Jason contributed not a little to the acceptance of the name of Jesus and to its apparent familiarity in ancient times. [Read more of this piece here.]

Source: Arthur Drews, Witnesses to the Historicity of Jesus,trans. Joseph McCabe (Chicago: Open Court Publishing, 1912).

J. Rendel Harris argreed, speculating that the Bible incorporates parts of the myth of Jason and Medea, specifically where Medea annoints Jason with an unguent to protect him from the flaming bulls, as Jesus is also annointed with oil:

Is it possible that the Gospel itself has been Jasonized by the insertion of a story in imitation of or in parallelism to the anointing of Jason? [...] [W]e are dealing with legendary matter that is trying to make itself historical. If that should be the right interpretation, there is no likelier quarter in which to seek for the origin of the story than in the tale of Jason and Medea. [Read more of this piece here.]

Source: Rendel Harris, Boanerges (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1913).

JASON (’Ιάσων, he that will cure, originally the name of the leader of the Argonauts), a Common Greek name, which was frequently adopted by Hellenizing Jews as the equivalent of Jesus, Joshua (’Ιησούς; comp. Josephus, Ant. xii, 5,1; Aristeas, Hist. apud Hody, p. 7), probably with some reference to its supposed connection with ιάσϑαι (i. e. the healer). A parallel change occurs in Alcimus (Eliakim), while Nicolaus, Dositheus, Menelaus, etc, were direct translations of Hebrew names. It occurs with reference to several men in the Apocrypha, and one in the New Testament.

Source: John McClintock and James Strong, Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological and Ecclesiastical Literature, vol. 4 (New York Harper & Bros., 1872), s.v. "Jason."

The German scholar Arthur Drews took this still further, arguing that Jason was the inspiration for the myth of Jesus:

The name [Jesus/Joshua] was fairly common among the Jews, and in this connection it is equivalent among the Hellenistic Jews to the name Jason or Jasios, which again is merely a Greek version of Jesus. […] Here again the idea of healing and saving is combined in the name, and would easily lead to the giving of the name to the saviour of the Jewish mystery-cult. Epiphanius clearly perceived this connection when he translated the name Jesus "healer" or "physician" (curator, therapeutes). It is certain that this allusion to the healing activity of the servant of God and his affinity with the widely known Jason contributed not a little to the acceptance of the name of Jesus and to its apparent familiarity in ancient times. [Read more of this piece here.]

Source: Arthur Drews, Witnesses to the Historicity of Jesus,trans. Joseph McCabe (Chicago: Open Court Publishing, 1912).

J. Rendel Harris argreed, speculating that the Bible incorporates parts of the myth of Jason and Medea, specifically where Medea annoints Jason with an unguent to protect him from the flaming bulls, as Jesus is also annointed with oil:

Is it possible that the Gospel itself has been Jasonized by the insertion of a story in imitation of or in parallelism to the anointing of Jason? [...] [W]e are dealing with legendary matter that is trying to make itself historical. If that should be the right interpretation, there is no likelier quarter in which to seek for the origin of the story than in the tale of Jason and Medea. [Read more of this piece here.]

Source: Rendel Harris, Boanerges (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1913).

Jacob and Rachel

The story of Jason and Medea has been compared to that of Jacob and Rachel in Genesis 29:1-30. In the Biblical story, Jacob travels to the "east" as does Jason, finding a beautiful maiden associated with sheep (just like Medea) and must undergo ordeals at the hand of a duplicitous and ruthless father (just like Aeetes) to win his intended bride. While Jason divorces Medea and takes up with Glauce, Jacob bigamously marries two sisters in order to have the bride he wants. This comparison appears in Bruce Louden's Homer's Odyssey and the Near East (2001) an is alluded to in other works.

Genesis 29:1-30

Then Jacob continued on his journey and came to the land of the eastern peoples. There he saw a well in the open country, with three flocks of sheep lying near it because the flocks were watered from that well. The stone over the mouth of the well was large. When all the flocks were gathered there, the shepherds would roll the stone away from the well’s mouth and water the sheep. Then they would return the stone to its place over the mouth of the well.

Jacob asked the shepherds, “My brothers, where are you from?”

“We’re from Harran,” they replied.

He said to them, “Do you know Laban, Nahor’s grandson?”

“Yes, we know him,” they answered.

Then Jacob asked them, “Is he well?”

“Yes, he is,” they said, “and here comes his daughter Rachel with the sheep.”

“Look,” he said, “the sun is still high; it is not time for the flocks to be gathered. Water the sheep and take them back to pasture.”

“We can’t,” they replied, “until all the flocks are gathered and the stone has been rolled away from the mouth of the well. Then we will water the sheep.”

While he was still talking with them, Rachel came with her father’s sheep, for she was a shepherd. When Jacob saw Rachel daughter of his uncle Laban, and Laban’s sheep, he went over and rolled the stone away from the mouth of the well and watered his uncle’s sheep. Then Jacob kissed Rachel and began to weep aloud. He had told Rachel that he was a relative of her father and a son of Rebekah. So she ran and told her father.

As soon as Laban heard the news about Jacob, his sister’s son, he hurried to meet him. He embraced him and kissed him and brought him to his home, and there Jacob told him all these things. Then Laban said to him, “You are my own flesh and blood.”

After Jacob had stayed with him for a whole month, Laban said to him, “Just because you are a relative of mine, should you work for me for nothing? Tell me what your wages should be.”

Now Laban had two daughters; the name of the older was Leah, and the name of the younger was Rachel. Leah had weakeyes, but Rachel had a lovely figure and was beautiful. Jacob was in love with Rachel and said, “I’ll work for you seven years in return for your younger daughter Rachel.”

Laban said, “It’s better that I give her to you than to some other man. Stay here with me.” So Jacob served seven years to get Rachel, but they seemed like only a few days to him because of his love for her.

Then Jacob said to Laban, “Give me my wife. My time is completed, and I want to make love to her.”

So Laban brought together all the people of the place and gave a feast. But when evening came, he took his daughter Leah and brought her to Jacob, and Jacob made love to her. And Laban gave his servant Zilpah to his daughter as her attendant.

When morning came, there was Leah! So Jacob said to Laban, “What is this you have done to me? I served you for Rachel, didn’t I? Why have you deceived me?”

Laban replied, “It is not our custom here to give the younger daughter in marriage before the older one. Finish this daughter’s bridal week; then we will give you the younger one also, in return for another seven years of work.”

And Jacob did so. He finished the week with Leah, and then Laban gave him his daughter Rachel to be his wife. Laban gave his servant Bilhah to his daughter Rachel as her attendant. Jacob made love to Rachel also, and his love for Rachel was greater than his love for Leah. And he worked for Laban another seven years.

Genesis 29:1-30

Then Jacob continued on his journey and came to the land of the eastern peoples. There he saw a well in the open country, with three flocks of sheep lying near it because the flocks were watered from that well. The stone over the mouth of the well was large. When all the flocks were gathered there, the shepherds would roll the stone away from the well’s mouth and water the sheep. Then they would return the stone to its place over the mouth of the well.

Jacob asked the shepherds, “My brothers, where are you from?”

“We’re from Harran,” they replied.

He said to them, “Do you know Laban, Nahor’s grandson?”

“Yes, we know him,” they answered.

Then Jacob asked them, “Is he well?”

“Yes, he is,” they said, “and here comes his daughter Rachel with the sheep.”

“Look,” he said, “the sun is still high; it is not time for the flocks to be gathered. Water the sheep and take them back to pasture.”

“We can’t,” they replied, “until all the flocks are gathered and the stone has been rolled away from the mouth of the well. Then we will water the sheep.”

While he was still talking with them, Rachel came with her father’s sheep, for she was a shepherd. When Jacob saw Rachel daughter of his uncle Laban, and Laban’s sheep, he went over and rolled the stone away from the mouth of the well and watered his uncle’s sheep. Then Jacob kissed Rachel and began to weep aloud. He had told Rachel that he was a relative of her father and a son of Rebekah. So she ran and told her father.

As soon as Laban heard the news about Jacob, his sister’s son, he hurried to meet him. He embraced him and kissed him and brought him to his home, and there Jacob told him all these things. Then Laban said to him, “You are my own flesh and blood.”

After Jacob had stayed with him for a whole month, Laban said to him, “Just because you are a relative of mine, should you work for me for nothing? Tell me what your wages should be.”

Now Laban had two daughters; the name of the older was Leah, and the name of the younger was Rachel. Leah had weakeyes, but Rachel had a lovely figure and was beautiful. Jacob was in love with Rachel and said, “I’ll work for you seven years in return for your younger daughter Rachel.”

Laban said, “It’s better that I give her to you than to some other man. Stay here with me.” So Jacob served seven years to get Rachel, but they seemed like only a few days to him because of his love for her.

Then Jacob said to Laban, “Give me my wife. My time is completed, and I want to make love to her.”

So Laban brought together all the people of the place and gave a feast. But when evening came, he took his daughter Leah and brought her to Jacob, and Jacob made love to her. And Laban gave his servant Zilpah to his daughter as her attendant.

When morning came, there was Leah! So Jacob said to Laban, “What is this you have done to me? I served you for Rachel, didn’t I? Why have you deceived me?”

Laban replied, “It is not our custom here to give the younger daughter in marriage before the older one. Finish this daughter’s bridal week; then we will give you the younger one also, in return for another seven years of work.”

And Jacob did so. He finished the week with Leah, and then Laban gave him his daughter Rachel to be his wife. Laban gave his servant Bilhah to his daughter Rachel as her attendant. Jacob made love to Rachel also, and his love for Rachel was greater than his love for Leah. And he worked for Laban another seven years.

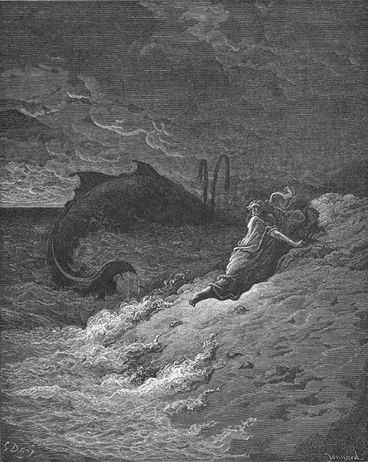

Jonah and the Whale

Jonah 1:17; 2:1, 10:

Now the LORD provided a huge fish to swallow Jonah, and Jonah was in the belly of the fish three days and three nights. From inside the fish Jonah prayed to the LORD his God. And the LORD commanded the fish, and it vomited Jonah onto dry land.

In 1995, Gildas Hamel, then a professor of French (now of Jewish studies), proposed that the story of Jonah was an elaborate parody of the story of Jason and the Argonauts as it was known to the Hebrews of Joppa in the middle of the first millennium BCE ("Taking the Argo to Nineveh," Judaism 44, no. 3 [1995]). He argued that Jonah (Greek: Ionas) was considered an anagram of Jason (Greek: Iason). Further, Jonah means "dove," which bird Jason used to sail through the Clashing Rocks. Both heroes sail on ships with a large crew, and both cross over the water on a mission. Both have aid from the divine. Jason, on the Douris cup, is seen to be swallowed by the dragon; and Jonah is swallowed by the great fish. Finally, Jonah is sheltered by a divine plant, similar to the herbal magic used by Medea or the tree on which the Fleece itself hung.

While this is the longest and most detailed examination of the parallels between the two heroes, such similarities have been noted since at least the nineteenth century. A handbook to the museums of Rome, for example, described the similarities between a depiction of Jonah on a sarcophagus in the Lateran Museum and the famous Douris cup image of Jason and the dragon:

Story of Jonah; in the centre a double figure of the whale placed with classical symmetry; the one towards the [left] receives with open mouth Jonah, who is being cast from the ship; the one turned to the [right] vomits him on land; above this, Jonah—a classical type of figure—lies at ease under the gourd; other scenes in the life of Jonah. The figure of the whale vomiting Jonah has a classical prototype in the dragon vomiting forth Jason on a fine red figure vase in the Museo Gregoriano.

Source: A Handbook of Rome and the Campagna, 16th ed. (London: John Murray, 1899), 129.

Now the LORD provided a huge fish to swallow Jonah, and Jonah was in the belly of the fish three days and three nights. From inside the fish Jonah prayed to the LORD his God. And the LORD commanded the fish, and it vomited Jonah onto dry land.

In 1995, Gildas Hamel, then a professor of French (now of Jewish studies), proposed that the story of Jonah was an elaborate parody of the story of Jason and the Argonauts as it was known to the Hebrews of Joppa in the middle of the first millennium BCE ("Taking the Argo to Nineveh," Judaism 44, no. 3 [1995]). He argued that Jonah (Greek: Ionas) was considered an anagram of Jason (Greek: Iason). Further, Jonah means "dove," which bird Jason used to sail through the Clashing Rocks. Both heroes sail on ships with a large crew, and both cross over the water on a mission. Both have aid from the divine. Jason, on the Douris cup, is seen to be swallowed by the dragon; and Jonah is swallowed by the great fish. Finally, Jonah is sheltered by a divine plant, similar to the herbal magic used by Medea or the tree on which the Fleece itself hung.

While this is the longest and most detailed examination of the parallels between the two heroes, such similarities have been noted since at least the nineteenth century. A handbook to the museums of Rome, for example, described the similarities between a depiction of Jonah on a sarcophagus in the Lateran Museum and the famous Douris cup image of Jason and the dragon:

Story of Jonah; in the centre a double figure of the whale placed with classical symmetry; the one towards the [left] receives with open mouth Jonah, who is being cast from the ship; the one turned to the [right] vomits him on land; above this, Jonah—a classical type of figure—lies at ease under the gourd; other scenes in the life of Jonah. The figure of the whale vomiting Jonah has a classical prototype in the dragon vomiting forth Jason on a fine red figure vase in the Museo Gregoriano.

Source: A Handbook of Rome and the Campagna, 16th ed. (London: John Murray, 1899), 129.

Freethinker Singleton Waters Davis tried to find a rational explanation for Bible myths and in so doing imagined that mythology was astronomical in nature, with myths telling the story of the sun's passage through the constellations. Thus, Jason and Jonah were connected in describing the sun's journey through the constellation Argo to, for Jonah, Cetus or Pisces, and for Jason, Aries:

Jonah (dove, the sun) was to go to Nineveh—literally fish city, that is, astrologically, the zodiacal constellation or sign Pisces, The Fishes, the last sign in the winter arc of the sun's ecliptic, and at the feet of the zodiacal Man (see almanac). The account of Jonah's sea voyage begins at the autumnal equinox, and the place where Noah entered the ark; and the two stories, as well as those of Jesus stilling the tempest and the shipwreck of Paul, are but variants of the same myth. This "ship" or "ark" is the arc of the sun's ecliptic extending from the fall equinox to that of spring, which the sun apparently traverses during winter—the rainy season, the sea of the year—symbolized in the southern heavens, the sea of the sky, by the constellation of the ship At go navis. This arc of the ecliptic, and so symbolized, is the ark of Noah, the "ship" in which Jesus was when, like Jonah, he lay asleep when a tempest arose which he was called upon to still; the same ship in which Paul, at first called Saul {sol, sun), and a variant of the Greek-Roman sun-god Apollo, sailed when he had such a tempestuous voyage, and like Noah, Jonah and Jesus, finally got safely onto "dry land;" the same ship, Argo, in which Jason (the same name, etymologically, as Jesus) and his companions went to Colchis in search of the Golden Fleece (sun in Aries, the Ram of the zodiac, in which the spring equinox occurred). Now notice this curious thing: in all these stories the storm is an important part, the voyages all end at the vernal equinox, and we of our boasted modern enlightenment still speak of the "equinoctial storm" of the spring season!

Source: Singleton Waters Davis, "How 'The Whale' Swallows Jonah," Humanitarian Review 1, no. 5 (1903): 131.

Jonah (dove, the sun) was to go to Nineveh—literally fish city, that is, astrologically, the zodiacal constellation or sign Pisces, The Fishes, the last sign in the winter arc of the sun's ecliptic, and at the feet of the zodiacal Man (see almanac). The account of Jonah's sea voyage begins at the autumnal equinox, and the place where Noah entered the ark; and the two stories, as well as those of Jesus stilling the tempest and the shipwreck of Paul, are but variants of the same myth. This "ship" or "ark" is the arc of the sun's ecliptic extending from the fall equinox to that of spring, which the sun apparently traverses during winter—the rainy season, the sea of the year—symbolized in the southern heavens, the sea of the sky, by the constellation of the ship At go navis. This arc of the ecliptic, and so symbolized, is the ark of Noah, the "ship" in which Jesus was when, like Jonah, he lay asleep when a tempest arose which he was called upon to still; the same ship in which Paul, at first called Saul {sol, sun), and a variant of the Greek-Roman sun-god Apollo, sailed when he had such a tempestuous voyage, and like Noah, Jonah and Jesus, finally got safely onto "dry land;" the same ship, Argo, in which Jason (the same name, etymologically, as Jesus) and his companions went to Colchis in search of the Golden Fleece (sun in Aries, the Ram of the zodiac, in which the spring equinox occurred). Now notice this curious thing: in all these stories the storm is an important part, the voyages all end at the vernal equinox, and we of our boasted modern enlightenment still speak of the "equinoctial storm" of the spring season!

Source: Singleton Waters Davis, "How 'The Whale' Swallows Jonah," Humanitarian Review 1, no. 5 (1903): 131.