THE SOWN-MEN

(Spartoi)

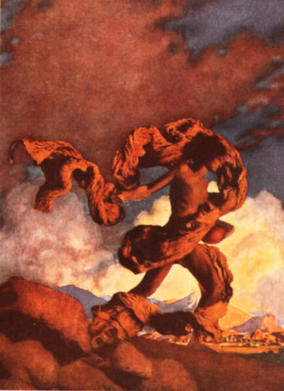

Cadmus sows dragon's teeth, Maxfield Parrish, 1908.

The motif of the Spartoi appears in two Greek myths, that of Jason and that of Kadmos. The Greeks explained this coincidence by suggesting that after Kadmos killed Ares' dragon, the dragon's teeth were divided, with half going to Kadmos and half to Aeetes, who later forced Jason to sow them.

Kadmos (Cadmus) and the Spartoi

William Sherwood Fox

The Mythology of All Races, vol. 1: Greek and Roman (1916)

Kadmos. — Agenor, a great-grandson of Io, established himself in Phoinikia, where he had a daughter named Europe, whom Zeus one day carried away to Crete by force. On her disappearance Agenor sent his wife and sons throughout the neighbouring lands in quest of her and ordered them not to return without her, but all failed in their errand, and, fearful of Agenor's anger, they resolved never to go back home, Phoinix settling in a district of Phoinikia, Kilix in Kilikia, and Thasos, Kadmos, and their mother Telephassa in Thrace. After the death of Telephassa, Kadmos felt free to continue his search for Europe, and going to Delphoi he inquired of the oracle concerning her. The god commanded him to cease worrying over his sister and to turn his thoughts into another channel, bidding him to follow a heifer which he would find outside the shrine and to establish a city on the spot where she would first lie down to rest. In obedience to the divine command Kadmos journeyed after the animal across Phokis until at length she sought repose beside a hill in the heart of Boiotia, and there he founded Thebes.

Desiring to sacrifice the cow to Athene, Kadmos dispatched a number of his men to draw water for the rites from the spring Areia, but most of them were killed by the dragon, the issue of Ares, which guarded the water, whereupon Kadmos himself slew the beast and at the suggestion of Athene scattered the teeth broadcast over the earth as a farmer strews his grain. From the teeth sprang a host of armed men who were called Spartoi ("Scattered") from the strange manner of their birth. At the sight of these warriors suddenly gathering about him, Kadmos was stricken with fear and began to hurl stones at them; and they, thinking that the missiles were thrown by their fellows, murderously set upon one another until only five of them were left alive. For his part in this tragedy Kadmos was bound in servitude to Ares for eight years, but at the end of this period Athene bestowed the kingship upon him and with the surviving Spartoi he began to build up the city of Thebes. Zeus gave him in marriage Harmonia, the daughter of Ares and Aphrodite, and all the gods came down from Olympos to attend the nuptials and brought with them rare and costly gifts, Kadmos's own presents to his bride being a robe and the necklace, wrought originally by Hephaistos, which Zeus had formerly given to Europe. To Kadmos and Harmonia were born a son, Polydoros, and four daughters, Semele, Ino, Agave, and Autonoe.

The following entries from the Dictionary of Phrase and Fable describe how the myth of the Spartoi entered everyday English.

E. Cobham Brewer

Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (1898)

Dragon's teeth. Subjects of civil strife; whatever rouses citizens to rise in arms. The allusion is to the dragon that guarded the well of Ares. Cadmus slew it, and sowed some of the teeth, from which sprang up the men called Spartans [Spartoi], who all killed each other except five, who were the ancestors of the Thebans. Those teeth which Cadmus did not sow came to the possessiou of Aeetes, King of Colchis; and one of the tasks he enjoined Jason was to sow these teeth and slay the armed warriors that rose therefrom.

To sow dragon's teeth. To foment contentions; to stir up strife or war. The reference is to the classical story of Jason or that of Cadmus, both of whom sowed the teeth of a dragon which he had slain, and from these teeth sprang up armies of fighting men, who attacked each other in fierce fight. Of course, the figure means that quarrels often arise out of a contention supposed to have been allayed (or slain). The Philistines sowed dragons' teeth when they took Samson, bound him, and put out his eyes. The ancient Britons sowed dragons' teeth when they massacred the Danes on St. Bryce's Day.

Sources: E. Cobham Brewer, Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, new ed. (Philadelphia: Henry Altemus Company, 1898); William Sherwood Fox, The Mythology of All Races, vol. 1: Greek and Roman, ed. Louis Herbert Gray (Boston: Marshall Jones Company, 1916).

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Kadmos (Cadmus) and the Spartoi

William Sherwood Fox

The Mythology of All Races, vol. 1: Greek and Roman (1916)

Kadmos. — Agenor, a great-grandson of Io, established himself in Phoinikia, where he had a daughter named Europe, whom Zeus one day carried away to Crete by force. On her disappearance Agenor sent his wife and sons throughout the neighbouring lands in quest of her and ordered them not to return without her, but all failed in their errand, and, fearful of Agenor's anger, they resolved never to go back home, Phoinix settling in a district of Phoinikia, Kilix in Kilikia, and Thasos, Kadmos, and their mother Telephassa in Thrace. After the death of Telephassa, Kadmos felt free to continue his search for Europe, and going to Delphoi he inquired of the oracle concerning her. The god commanded him to cease worrying over his sister and to turn his thoughts into another channel, bidding him to follow a heifer which he would find outside the shrine and to establish a city on the spot where she would first lie down to rest. In obedience to the divine command Kadmos journeyed after the animal across Phokis until at length she sought repose beside a hill in the heart of Boiotia, and there he founded Thebes.

Desiring to sacrifice the cow to Athene, Kadmos dispatched a number of his men to draw water for the rites from the spring Areia, but most of them were killed by the dragon, the issue of Ares, which guarded the water, whereupon Kadmos himself slew the beast and at the suggestion of Athene scattered the teeth broadcast over the earth as a farmer strews his grain. From the teeth sprang a host of armed men who were called Spartoi ("Scattered") from the strange manner of their birth. At the sight of these warriors suddenly gathering about him, Kadmos was stricken with fear and began to hurl stones at them; and they, thinking that the missiles were thrown by their fellows, murderously set upon one another until only five of them were left alive. For his part in this tragedy Kadmos was bound in servitude to Ares for eight years, but at the end of this period Athene bestowed the kingship upon him and with the surviving Spartoi he began to build up the city of Thebes. Zeus gave him in marriage Harmonia, the daughter of Ares and Aphrodite, and all the gods came down from Olympos to attend the nuptials and brought with them rare and costly gifts, Kadmos's own presents to his bride being a robe and the necklace, wrought originally by Hephaistos, which Zeus had formerly given to Europe. To Kadmos and Harmonia were born a son, Polydoros, and four daughters, Semele, Ino, Agave, and Autonoe.

The following entries from the Dictionary of Phrase and Fable describe how the myth of the Spartoi entered everyday English.

E. Cobham Brewer

Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (1898)

Dragon's teeth. Subjects of civil strife; whatever rouses citizens to rise in arms. The allusion is to the dragon that guarded the well of Ares. Cadmus slew it, and sowed some of the teeth, from which sprang up the men called Spartans [Spartoi], who all killed each other except five, who were the ancestors of the Thebans. Those teeth which Cadmus did not sow came to the possessiou of Aeetes, King of Colchis; and one of the tasks he enjoined Jason was to sow these teeth and slay the armed warriors that rose therefrom.

To sow dragon's teeth. To foment contentions; to stir up strife or war. The reference is to the classical story of Jason or that of Cadmus, both of whom sowed the teeth of a dragon which he had slain, and from these teeth sprang up armies of fighting men, who attacked each other in fierce fight. Of course, the figure means that quarrels often arise out of a contention supposed to have been allayed (or slain). The Philistines sowed dragons' teeth when they took Samson, bound him, and put out his eyes. The ancient Britons sowed dragons' teeth when they massacred the Danes on St. Bryce's Day.

Sources: E. Cobham Brewer, Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, new ed. (Philadelphia: Henry Altemus Company, 1898); William Sherwood Fox, The Mythology of All Races, vol. 1: Greek and Roman, ed. Louis Herbert Gray (Boston: Marshall Jones Company, 1916).

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons.

From THE NIGHT OF THE GODS

John O'Neill

1893

In a very strange book, JOHN O'NEILL attempted to argue that the entirety of world mythology could be explained by the movements of the constellations in the sky, about which the ancients told stories that encoded astronomical information, and argument that found latter-day fame in a different guise in Santillana and von Deschend's Hamlet's Mill. However, the Victorian reviewers were right when the Times of London wrote that the book was "a monument of ill-directed and imperfectly co-ordinated energy— albeit, the product of much research and the work of an ingenious mind." In this excerpt, O'Neill attempts to relate the Spartoi to prehistoric weaponry, the Golden Fleece, and the axis mundi. It is an interesting, though probably very wrong, reading. Since O'Neill used his own unique spelling and language, I have standardized the spelling of names (he liked to capitalize random letters to deduce imaginary etymologies); I have also provided a translation for the Latin text included and removed a few extraneous non-English appositives.

One of the leading myths which we have not hitherto been able to explain to ourselves is the sowing of the serpent's teeth by Kadmos son of Agenor. Apollonios of Rhodes said that thereafter he "founded a race of earthborn γαιήγενεΐς men from the remnant left after the harvesting of Ares' spear;" which is not self-explanatory. Can it refer to teeth having been archaically used for spearheads (for we are certain that they were used in these Egyptian reaping-hooks); and also to the flint weapon-points being found everywhere as if sown broadcast? And would this throw any new light on Samson's (reaping?) exploit with the "new jawbone-of-an-ass?" (Judges 15:15)

On correcting the proof of the foregoing sentence, I find in Seyffert's Mythological Dictionary that "the invention of the saw, which he copied from the chinbone of a snake," is ascribed to Talos, the nephew of Daidalos. Now when Kadmos, helped by Athene Όγκα, killed the monstrous python-serpent of Ares—for this drakon was depicted as a great boa in ancient art—either the goddess or he (by her advice) sowed its teeth, which produced the armed Theban giants called Spartoi, whose name was brought, by what I suggest was a punning shot, from σπείρω, sow.

The root is spar, but another view may be held, that the real origin of Spartoi, and also of σπάρτος, esparto-grass, still exists in the obvious English words spar (a bar, pole, yard), spear, spur, "Aryan" spara a dart. Nor does the original sense of σπείρω, σπάρω, to beget, to shake, seem to have been merely the scattering of vegetable seeds with the hand. The words may have existed before agriculture was dreamt of.

The idea I throw out is that what were fabled to have been sown were the flint weapons, the dartheads and spearheads, that were found in the soil as if they had been sown broadcast.

Arma antiqua manus ungues dentesque fuerunt,

et lapides et item silvarum fragmina rami.

(Lucretius v, 1282.)

The first weapons of mankind were the hands, nails, and teeth;

also stones, and branches of trees, the fragments of the woods.

(Trans. John Selby Watson, 1851)

(This, in one aspect, is a doublet of Deukalion and Pyrrha's creation of mankind by throwing stones.) The next step in my theory is that these flints were mixed up with those put into jawbone-sickles (and saws) to replace the natural teeth, and that something like this is the rationale of the myth. And we must not forget that Demeter, as the universal mother produced the first men.

The sowing of the Roman Campus Martius by Tarquinius Superbus (the High Turner of the heavens) is an obvious mythic doublet of this story of Kadmos.

If there be anything in this speculating, then we may perhaps flash another light on the above "harvesting " in the Argonautika. A legend of Corcyra (see p. 33) anciently Drepane, related by Aristotle, said that Demeter there taught the Titans to harvest with a δρεπάνη or sickle that she had begged of Poseidon, which drepane she then buried, and so gave its name to the island.

In the following century however, Timaios (260 B.C.) said that the name came from the drepane with which Kronos maimed Ouranos, or Zeus cut Kronos.

A similar story was told of Cape Drepanon in Sicily; and we here may clearly have what was wanting, the putting into the ground of the teeth or flint-teeth in the jaw-sickle. The drepane, plucker, from δρέπω,pluck, must have been a very primitive article, its name belonging to a previous hand-plucking of the ears.

If we are to see a celestial meaning in the Titan's harvest, it was perhaps a doublet of the shearing or skinning idea, of the golden fleece, and was thus a figure for the golden grain of the starry heavens.

I must not omit to note that the helper of Kadmos was probably not Athene at all, but some local goddess who became absorbed in Athene; for the name Όγκα is the obvious feminine of Όγκως, who was similarly made a son of Apollo. Now one sense of όγκως was a barb—modern Greek αγκάθιthorn (compare ακανθα), αγκίστρι hook. We still say “toothed " for barbed, w hich in modern Greek is οδοντατόσ.

Source: John O'Neill, The Night of the Gods: An Inquiry into Cosmic and Cosmogonic Mythology and Symoblism, vol. 1 (London: Harrison and Sons, 1893), 82-84.

One of the leading myths which we have not hitherto been able to explain to ourselves is the sowing of the serpent's teeth by Kadmos son of Agenor. Apollonios of Rhodes said that thereafter he "founded a race of earthborn γαιήγενεΐς men from the remnant left after the harvesting of Ares' spear;" which is not self-explanatory. Can it refer to teeth having been archaically used for spearheads (for we are certain that they were used in these Egyptian reaping-hooks); and also to the flint weapon-points being found everywhere as if sown broadcast? And would this throw any new light on Samson's (reaping?) exploit with the "new jawbone-of-an-ass?" (Judges 15:15)

On correcting the proof of the foregoing sentence, I find in Seyffert's Mythological Dictionary that "the invention of the saw, which he copied from the chinbone of a snake," is ascribed to Talos, the nephew of Daidalos. Now when Kadmos, helped by Athene Όγκα, killed the monstrous python-serpent of Ares—for this drakon was depicted as a great boa in ancient art—either the goddess or he (by her advice) sowed its teeth, which produced the armed Theban giants called Spartoi, whose name was brought, by what I suggest was a punning shot, from σπείρω, sow.

The root is spar, but another view may be held, that the real origin of Spartoi, and also of σπάρτος, esparto-grass, still exists in the obvious English words spar (a bar, pole, yard), spear, spur, "Aryan" spara a dart. Nor does the original sense of σπείρω, σπάρω, to beget, to shake, seem to have been merely the scattering of vegetable seeds with the hand. The words may have existed before agriculture was dreamt of.

The idea I throw out is that what were fabled to have been sown were the flint weapons, the dartheads and spearheads, that were found in the soil as if they had been sown broadcast.

Arma antiqua manus ungues dentesque fuerunt,

et lapides et item silvarum fragmina rami.

(Lucretius v, 1282.)

The first weapons of mankind were the hands, nails, and teeth;

also stones, and branches of trees, the fragments of the woods.

(Trans. John Selby Watson, 1851)

(This, in one aspect, is a doublet of Deukalion and Pyrrha's creation of mankind by throwing stones.) The next step in my theory is that these flints were mixed up with those put into jawbone-sickles (and saws) to replace the natural teeth, and that something like this is the rationale of the myth. And we must not forget that Demeter, as the universal mother produced the first men.

The sowing of the Roman Campus Martius by Tarquinius Superbus (the High Turner of the heavens) is an obvious mythic doublet of this story of Kadmos.

If there be anything in this speculating, then we may perhaps flash another light on the above "harvesting " in the Argonautika. A legend of Corcyra (see p. 33) anciently Drepane, related by Aristotle, said that Demeter there taught the Titans to harvest with a δρεπάνη or sickle that she had begged of Poseidon, which drepane she then buried, and so gave its name to the island.

In the following century however, Timaios (260 B.C.) said that the name came from the drepane with which Kronos maimed Ouranos, or Zeus cut Kronos.

A similar story was told of Cape Drepanon in Sicily; and we here may clearly have what was wanting, the putting into the ground of the teeth or flint-teeth in the jaw-sickle. The drepane, plucker, from δρέπω,pluck, must have been a very primitive article, its name belonging to a previous hand-plucking of the ears.

If we are to see a celestial meaning in the Titan's harvest, it was perhaps a doublet of the shearing or skinning idea, of the golden fleece, and was thus a figure for the golden grain of the starry heavens.

I must not omit to note that the helper of Kadmos was probably not Athene at all, but some local goddess who became absorbed in Athene; for the name Όγκα is the obvious feminine of Όγκως, who was similarly made a son of Apollo. Now one sense of όγκως was a barb—modern Greek αγκάθιthorn (compare ακανθα), αγκίστρι hook. We still say “toothed " for barbed, w hich in modern Greek is οδοντατόσ.

Source: John O'Neill, The Night of the Gods: An Inquiry into Cosmic and Cosmogonic Mythology and Symoblism, vol. 1 (London: Harrison and Sons, 1893), 82-84.