THE ORIGINS OF ALL

RELIGIOUS WORSHIP

Charles François Dupuis

1795

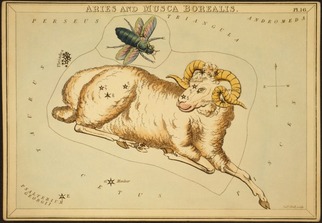

The constellation Aries, 1825 drawing.

CHARLES FRANÇOIS DUPUIS (1742-1809), a French savant; was a member of the Convention of the Council of the Five Hundred, and President of the Legislative Body during the Revolution period; devoted himself to the study of astronomy in connection with mythology, the result of which was published in his work in 12 vols., entitled "Origine de tous les Cultes, ou la Religion Universelle" (1795); he advocated the unity of the astronomical and religious myths of all nations. (Text adapted from the 1907 Nuttall Encyclopaedia.) In Chapter VIII, Dupuis explains his theory that the story of Jason primarily describes the path of the sun through the zodiac, with the constellations playing the roles of the characters in the myth.

CHAPTER VIII

The fable of Jason, the conqueror of the Ram of the golden fleece, or of the celestial sign, which, by its disengagement from the solar rays in the morning, announces the arrival of the Star of Day at the equinoctial Bull of spring, is alike famous in mythology, as the fiction of the twelve labours of the Sun under the name of Hercules, and that of its travels under that of Bacchus. This is again an allegorical poem, which belongs to another people, and which has been composed. by other priests, whose great Divinity was the Sun. It would seem to be the work of the Pelasgi of Thessaly, as the poem on Bacchus was that of, or had its origin with the people of Boeotia. Each nation, while worshipping the same God Sun under different names, had its priests and poets, who did not want to copy each other in their sacred cantos. The Jews celebrated this same equinoctial epoch, under the name of feast of the Lamb and of the triumph of the cherished people of God over the hostile people. It was also at that epoch, that the Hebrews, when delivered from oppression, passed into the promised land, into the abode of delight, the gate of which was opened to them by the sacrifice of the Lamb. The worshippers of Bacchus said of this Ram, or of this equinoctial Lamb, that it was the same, which in the desert in the midst of the Sands, caused the discovery of spring water, in order to refresh the army of Bacchus, as also loses with a stroke of his wand, made to spout out in the desert, in order to quench the thirst of his army. All these astronomical fables have a point of contact in the celestial sphere, and the horns of Moses resemble very much those of Ammon and of Bacchus.

We have already observed in the explanation we have given of the poem on Hercules, that this pretended hero, whose history explains itself entirely by Heaven, belonged to the expedition of the Argonauts, which is indicative enough of the character of this last fable: it is therefore still in Heaven, that we must follow the actors of this new poem, because one of the most distinguished heroes amongst them is in the Heavens, and that it is there, where the scene of all his adventures lays, that his image is located there as well as that of Jason, the leader of this wholly astronomical expedition. Amongst the constellations may also be found the vessel, on which the Argonauts had embarked, and which is still called the ship Argo; the famous Ram with the golden fleece, which is the first of the signs, may also be seen there; likewise the Dragon and the Bull, which guarded the fleece; the Twins Castor and Pollux, which were the principal heroes of this expedition; the same as Cepheus and the Centaur Chiron. The celestial images and the personages of the poem have such an affinity amongst each other, that the celebrated Newton thought, that he could draw from it an argument in order to prove, that the sphere had been composed since the expedition of the Argonauts, because most of its heroes, who are mentioned in that song, find themselves located in the Heavens. We shall not at all deny this perfect correspondence, not more than that, which is to be found between the Heavens and the pictures of the poem on Hercules and on Bacchus, but we shall draw from it only one consequence, which is, that the celestial figures were the common foundation, on which the poets worked, who gave them different; names, under which they made them figure in their poems.

There is not more reason to say, that these images were consecrated in the Heavens on the occasion of the expedition of the Argonauts, than it would be to assert, that they were so on the Occasion of the labours of Hercules, because the subjects of these two poems are to be found there likewise, and if they were put there for one of these fables, they could not have been so for the other, as the place would have been already occupied; because they are the same group of stars, but every one has sung them after his own fashion: hence the reason why they suit all these poems.

The conclusion of Newton could be only in so far of any force, as there should exist any certainty about the expedition of the Argonauts being a historical fact, and not a fiction similar to those, having Hercules, Bacchus, or Osiris and Isis and their travels for object, and we are very far from having that assurance. At the contrary, all is concurring to range it in the class of sacred fictions, because it is found intermingled with them in the depot of the ancient mythology of the Greeks, and that it has heroes and characters in common with those of these poems, which we have explained by astronomy. We shall therefore make use of the same key, in order to analyse this solar poem.

The poem on Jason does not comprehend the entire annual revolution of the Sun, like those of the Heracleid and of the Dionysiacs, which we have explained; but has only for object one of those epochs, in truth a very famous one, when this luminary, after overcoming winter, reaches the equinoctial point of spring, and enriches our hemisphere with all the blessings of the periodical vegetation. That is the time, when Jupiter, metamorphosed into a golden rain, created Perseus, whose image is placed over the celestial Ram, called the Ram with the golden fleece, the rich conquest of which was attributed to the Sun, the conqueror of Darkness and the redeemer of Nature.

It is this astronomical fact, this single annual phenomenon, which has been sung in the poem called "Argonautics." It is on that account, that this fact enter only partially in the solar poem upon Hercules, and forms. an episodical piece of the ninth labour, or of that, which corresponds to the celestial Ram. In the Argonautics on the contrary, it is a whole poem, which has one single subject. It is this poem, which we are going to analyse, and the relations of which with the Heavens we shall show, if not in detail, at least so far as the main point is concerned, which the genius of each poet has amplified and ornamented after his own fashion. The fable of Jason and of the Argonauts has been treated by several poets, by Epimenides, Orpheus, Apollonius of Rhodes and by Valerius Flaccus. We possess only the poems of the last three, and we shall analyse here only that of Apollonius, which is written in four cantos. All are supported by the same astronomical basis, which is reduced to very few elements.

We will recollect that Hercules in the labour corresponding to the Ram, before he arrives at the equinoctial Bull, is supposed as having embarked for the purpose of going to Colchis, in quest of the golden fleece. At the same epoch he freed a maiden exposed to a sea monster, as Andromeda was placed near the same Ram. He went then on board the ship Argo, one of the constellations, which establishes this same passage of the Sun to the Ram of the signs. Here we have therefore the given position of the Heavens for the epoch of this astronomical expedition. Such is the state of the sphere to be supposed at the time, when the poet sings the Sun under the name of Jason, and his conquests of the famous Ram. This supposition is confirmed, by what Theocritus tells us: that it was at the rising of the Pleiades and in the Spring, when the Argonauts embarked. Now, the Pleiades rise, when the Sun arrives towards the end of the Stars of the Ran, and when it enters the Bull, which is the sign, that corresponded in those remote periods to the equinox. This fact being established, let us examine what constellations in the morning and evening hours fixed this important epoch.

We find in the evening at the eastern rim the celestial vessel, called by the Ancients the ship of the Argonauts. It is followed {p.178} in its rise by the Serpentarius called Jason: between them is the Centaur Chiron, who educated Jason, and above Jason is the Lyre of Orpheus, preceded by the celestial Hercules, one of the Argonauts.

At the West, we see the Dioscuri Castor and Pollux, the leaders of this expedition with Jason. On the next day in the morning we perceive at the Eastern rim of the horizon, the celestial Ram, disengaging itself from the rays of the Sun with the Pleiades, Perseus, Medusa and the charioteer or Absyrtus, while at the West, the Serpentarius Jason and his serpent descend into the bosom of the waves after the celestial Virgin. In the East Medusa is rising, who plays here the role of Medea, and who being placed above the Ram, seems to give up its rich fleece to Jason while the Sun eclipses with its rays the Bull which follows the Ram, and the Sea Dragon placed below, who seems to guard this precious deposit. Those are, or very nearly so, the principal celestial aspects, which are offered to our views: we have sketched them on one of the planispheres of our larger work, destined to facilitate the understanding of our explanations. The reader ought to recollect above all, these various aspects, in order to recognize them under the allegorical veil, with which. the poet is covering them, by mixing continually geographical descriptions and astronomical positions, which have a foundation of truth, with stories, which are entirely feigned. Almost all the details of the poem are the fruits of the imagination of the poet.

ARGONAUTICS

CANTO I

Apollonius commences with an invocation of the God himself, which he is going to sing, or of the Sun, the Chief of the Muses, and the tutelar Divinity of the poets. At the first verses or in the proposition, he establishes the object of the sole action of his poem. He is going, he says, to celebrate the glory of ancient heroes, who by the order of King Pelias, had embarked on board the ship Argo, the very same, of which the image is in the Heavens, and who have gone in quest of the golden fleece of a Ram, which is likewise amongst the constellations. It is through the Cyarnaean rocks and by the entrance of the Pontus, that he marks the route of these intrepid travellers.

An oracle had informed Pelias, that he would perish by the hands of a man, whom he had ascertained since to be Jason. In order to avoid the effects of this sad prediction, he proposed to the latter a perilous expedition, from which he hoped, he would never be able to return. The proposition was, to go to Colchis to make the conquest of a golden fleece, which was in possession of Æetes, a son of the Sun and King of that country. The poet begins his subject by enumerating the names of the various heroes, the followers of Jason in the expedition. Amongst them Orpheus is noted; his society and example having been recommended to Jason by Chiron his tutor. The harmony of his songs would be useful, in order to soften the tediousness of his toilsome task. It will be observed that the Lyre of Orpheus is in the Heavens over the Serpentarius Jason, near a constellation, which is also called Orpheus. These three celestial images, Jason, Orpheus and the Lyre, rise together at, the setting in of Night and at the departure of Jason for his adventure. Such is the allegorical basis, which associates Orpheus with Jason.

Next to Orpheus comes Asterion, Typhys, the son of Phorbas, the pilot of the vessel; Hercules, Castor and Pollux, Augias, the son of the Sun and a great many other heroes, whose names we shall not mention here. Several of them are those of the constellations.

Behold those brave warriors on their way to the seashore in the midst of an immense concourse of people, praying Heaven for the success of their voyage, and already predicting the fall of Æetes, should he be obstinate enough to refuse to them the rich fleece, which they are inquest of in those remote regions. The women especially are in tears on account of their departure, and they commiserate the fate of old Æson, the father of Jason and of Alcimede, his mother.

The poet stops here, in order to draw a picture of the touching scene of this separation, and of the firmness of Jason, endeavouring to console those, who are dear to him. There is his mother, who while bathed in tears, embraces him fondly with tender expressions of her sorrows and fears. The women of her suite share her affliction; and the slaves carrying the armour of her son observe a gloomy silence and does, not raise their eyes. We feel, that all these descriptions and those which follow, have one single idea for basis, which is the departure of Jason, and his parting with his family. Since the Genius, charged with the guidance of the chariot of the Sun, has been personified, all the details of the action have emanated from the imagination of the poet, excepting those, which have in small numbers, some astronomical positions for basis, which the poet knew, how to invest with the charms of poetry and with the marvels of fiction.

Jason always firmly resolved, begs his mother to remember the flattering hopes, given to him by the oracle, and those which he himself has in the strength and courage of his heroic companions. He entreats her, to dry her tears, which might be taken by his companions as a sinister omen. Thus speaking he slips from her embraces, and soon he makes his appearance in the midst of a great crowd of people, like Apollo, when he marches along the shores of the Xanthus, in the midst of the sacred choirs. The multitude makes the air resound with loud exclamations, which are a good augury of success. Iphis, the old priestess of Diana conservatrix, takes him by the hand, which she kisses; but she is prevented from enjoying the. happiness to talk to him, so great is the crowd which presses around him.

Our hero has already arrived at the port of Pagasus, Where the ship Argo was at anchor, and where his companions were waiting for him. He summons a meeting and makes an allocution, in which he proposes, before any other thing, the election of a leader. Everybody has his eye upon Hercules, who however declines that honour, and declares that he would be opposed to anybody else's accepting the command, except him, who had brought them here together; that to him alone was due the honour. Hercules plays here a secondary roll, because the question here is not about the Sun, but about the Hercules constellation, which is his image, placed in the Heavens near the pole.

All approve this generous advice and Jason rises, in order to acknowledge his gratitude to the assembly; he announces that nothing shall now delay their departure. He invites them to make a sacrifice to the Divinity of the Sun or to Apollo under whose auspices they are going to embark, and in whose honour he causes an altar to be erected.

The poet enters then into some details about the preparations for the embarkation. They draw lots for the seats of the rowers. Hercules has that of the middle, and Tiphys takes his place at the helm.

The sacrifice then takes place, and Jason addresses a prayer to the Sun his grandfather, a Divinity, which is worshipped in the port, whence he starts. They immolate in its honour two Bulls, which fall under the blows of Hercules and of Ancaeus. Meanwhile the Day star had nearly reached its journey's end and touched at the moment, when Night was going to spread her gloomy veil over the country. The navigators sit down on the shore, where they are treated to supper and wine: they enliven their banquet with merry discourses. Jason alone appears to be thoughtful and profoundly occupied with the important cares, with which he is charged. Idas makes some insulting remarks to him with the approbation of the whole crowd. A dispute is at the point of breaking out, when Orpheus calms again the spirits by his harmonious songs on Nature and on the clearing up of chaos. They offer libations to the Gods and afterwards resign themselves to sleep.

Scarcely had the first rays of Day gilded the summit of mount Pelion, and the fresh breeze of morning commenced to agitate the surface of the waters, when Tiphys, the pilot of the vessel, awakens the crew, and urges it to go on board: they obey. Each one takes the place which chance had assigned him. Hercules is amidships, the weight of his body, when coming on board, made the vessel sink deeper into the water. They weigh anchor, and Jason takes once more a parting look of his country. The rowers play their oars in measure with the sounds of the Lyre of Orpheus, who by his songs keeps up their efforts. The wave, white with foam, is murmuring under the edge of the oar, and bubbles up under the keel of the vessel, leaving a long furrow behind. Thus far, only a departure is described with those circumstances, which are its usual accompaniment, and which depend upon the imagination of the poet.

The Gods had however that day fixed their eyes on the sea and on the vessel, which carried the flower of the heroes of their age; who were associates of the labours and the glory of Jason. The Nymphs of Pelion contemplated with astonishment the vessel constructed by the wise Minerva. Chiron, whose image is in the Heavens near the Sepentarius Jason, is descending to the seashore, where the foaming billow breaks, which comes to wet his feet. He encourages the navigators, and offers them his best wishes for their happy return.

By that time the Argonauts had passed beyond Cape Tissa, and the coasts of Thesssaly were lost in shadowy distance behind them. The poet gives a description of the Islands and Capes, near which they are passing, or which they discover, until they had approached the isle of Lemnos, where the Pleiad Hypsipyle reigned. He profits of the occasion, to narrate the famous adventure of the Lemniades, who had killed all the men of their island, with the exception of old Thoas, who had been saved by his daughter Hypsipyle, who became queen of the whole country. Compelled to cultivate their fields and to defend themselves with their own weapons, these women gave themselves up to agriculture and to the hard labour of warriors; they were able to repel the assaults of their neighbours; and they kept especially a good look out against the Thracians, whose vengeance they apprehended.

When they perceived the vessel Argo approaching their island, they rushed from the city in great haste to the seashore, in order to repel those strangers by force of arms, as they were taking them first for Thracians: in front of them marched the daughter of Thoas, covered with her father's amour. The Argonauts dispatched a herald to them in order to obtain admission into their island. They discussed the question in an assembly, which was convoked by the queen. She advised them, to send to these strangers all kinds of assistance in provisions, of which they might be in want, but on no account to receive them into their city. Polixo, another Pleiad, of which the poet makes here the nurse of Hypsipyle, opposes in part the opinion of the queen. She also wants to grant refreshments to these strangers; but moreover she requests, against the advice of the queen, that they be received into the city. She supports her proposition with this principal argument, that they could not any longer go on without men; she says, that for their own defence they were in want of them, and in order to repair the losses, which their population was undergoing every day. This speech is received with the loudest acclamations, and the assent is so general, as not to leave the slightest doubt, that every woman was in favour of it. It may be remarked here, that the intervention of two Pleiades, just at the very moment of the departure of Jason, contains an allusion to the conjunction of the stars of spring with the Sun, and which are in aspect with the Serpentarius Jason, which rises at their setting and sets when they are rising.

As Hypsipyle could no longer ignore the intention of the assembly, she dispatches Iphinoé to the Argonauts, in order to invite their Chief on her part to come to her palace, and to induce all his companions to accept lands and establishments in their island, Jason accepts the invitation, and in order to appear before the princess, he puts on a magnificent cloak, a gift of Minerva, which she had embroidered herself. There were delineated on it a long series of mythological subjects, amongst others the adventures of Phryxus and his Ram. Our hero takes in his hand also the lance, which Atalanta had made him a present of, when she received him on mount Menale.

Thus arrayed, Jason proceeds to the city, where the Pleiad held her court. Arrived at the gates, he found a crowd of the most distinguished women in attendance, in the midst of whom he advances with modest mien and cast down eyes, until he is introduced in the palace to the Princess. lie is placed on a seat in front of the queen, who looks at him blushingly and addresses him in affectionate language. But she conceals the actual reason of the want of men in her island; she feigns, that they had gone on an expedition to Thracia, and that, seduced by their captives, they had finally become tired of their spouses; that they had in consequence shut their gates upon them, and resolved on separation forever. Therefore, she added, there is no obstacle whatever existing against the establishment of you and your companions amongst us, and that you become the successors to the estates of Thoas my father. Go and report to the heroes, which accompany you my offers and let them enter our walls.

Jason thanks the Princess, and accepts one part of her proposals, namely the supply of provisions, which she promised: with regard to the sceptre of Thoas, he begs her to keep it, not because he disdains it, but because an important expedition calls him somewhere else.

Meanwhile loaded carts bring the presents of the queen to the vessel, where her good intentions towards the Argonauts are already known through the reports of Jason. The allurements of pleasure keep the Argonauts back on the island, and endear them to this charming country; but stern Hercules, who had remained on board with the better portion of his friends, calls them back to their duty and the glory, which awaits them on the shores of Colchis. His reproof is listened to by the company without murmur, and preparations for departure are made. The poet gives here a description of the distress of the women at the time of that separation, and of their best wishes for the success and happy return of these intrepid navigators. Hypsipyle is bathing with her tears the hands of Jason, and bids him a tender farewell. Wherever thou mayst dwell, she tells him, remember Hypsipyle, and before departing, tell me, what I shall do, if a child is born to me, the cherished fruit of our short-lived union.

Jason requests her, that in case she should be delivered of a son, to send him to Iolehos, near his father and mother, to whom he would be a source of consolation during his absence. Thus speaking, he forthwith leaps on board of his vessel, placing himself at the head of all his companions, who eagerly seize their oars. They cut the cable and the vessel is soon far away, with the isle of Lemnos in the distance. The Argonauts arrive at Samothracia, at the same place, where Cadmus, the same as the Serpentarius had landed under another name: it is that, which he takes in the Dionysiacs. There reigned Electra, another Pleiad: so we have now already three Pleiades put on the stage by the poet. Jason lets himself to be initiated into the mysteries of this island and proceeds on his route. We must now follow the Argonauts more on the Earth than in the Heavens. The poet having supposed, that it was in the East, and at the extremity of the Black Sea, that the celestial Ram rose at the time of the Sun's rising on the day of the equinox, he marks the route, which all vessels were presumed to follow, in order to arrive at those distant shores. It is therefore more a geographical, than an astronomical map, which has to serve us here as a guide.

In consequence of this supposition, we see the Argonauts pass between Thracia and the island of Imbros, sailing before the wind towards the Black Gulf, or the Gulf of Mlelas. They enter the Hellespont, leaving at their right mount Ida and the fields of Troas; they hug the shores of Abydos, of Percote, of Abarnis and of Lampsacus.

The neighbouring plain of the Isthmus was inhabited by the Doliones, whose Chief was Cysicus, the founder of their city. He was of Thessalian origin, and received therefore the Argonauts favourably, in as much as they were Greeks and their leader also a Thessalian. This host unfortunately perished afterwards in a night attack, in which the Argonauts and the Doliones by mistake engaged, when the former after their departure, were carried back by adverse winds. They made splendid funeral obsequies to this unfortunate Prince, and erected a tomb to him.

After having made a sacrifice to Cybele, the Argonauts quit again the harbour. They approach the Gulf of Cyanea and mount Arganthonium.

The Mysians, inhabiting these shores and placing entire confidence into the good behaviour of the Argonauts, gave them a friendly reception and furnished them with everything they wanted. While the whole crew is only intent on the pleasures of the banquet, Hercules leaves the vessel and goes into a neighbouring forest in order to cut there an oar, which might suit his hand better, because his own had been broken by the violence of the waves. After having searched for a long time, he discovers finally a fir tree, which he shakes by blows with his club, he then pulls it up and makes himself an oar out of it.

Young HIylas, who had accompanied him, had meanwhile penetrated somewhat far into the forest, in order to go in search of a fountain, for the purpose of procuring water for the hero, which he might want on his return.

The poet narrates on this occasion the well known story of this child, which is drowned in the fountain, where he was thrown by a Nymph, who had fallen in love with him, he gives also a description of the grief of Hercules, who from that time abandoned all idea of returning on board of the vessel.

Meanwhile the joining Star appeared on the summit of the neighbouring mountains, and a fresh breeze began to rise, when Tiphys admonished the Argonauts to re-embark, and to take advantage of the favourable wind.

They heave up the anchor, and are already coasting along Cape Posideon, when they are made aware of the absence of Hercules.

They were discussing the question of returning to Mysia, when Glaucus, a Marine Deity, raised his muddy head above the waves and addressed the Argonauts in order to calm their apprehensions. He tells them that it would be of no avail, to attempt, against the will of Jupiter, to carry Hercules to Colchis, as he had yet to accomplish his laborious career of the twelve labours; that therefore they ought to cease busying their minds any longer about him. He informs them of the fate of young Hylas, who had married a Water Nymph. Having ended his speech, the Marine God dives again to the bottom of the Sea, and leaves the Argonauts to proceed on their route.. They land the next day on a shore in the vicinity. Here ends the first Canto.

CANTO II

The navigators had landed in the country of the Bebrycians, where Amycus a son of Teptune, reigned. This ferocious Prince defied all strangers to the combat of the Cestus, and had already killed many of his neighbours. It will be observed that the poet, as soon as he makes the Argonauts arrive in a country, never fails to mention all the mythological traditions, belonging to the cities and to the people, of which he has occasion to speak; this forms a series of particular actions, which are allied with the principal or rather only action of the poem, which is the arrival at Colchis, and. the conquest of the famous golden fleece.

Amycus goes to meet the companions of Jason, he makes enquiries on the subject of their voyages, and addresses them in a threatening allocution. He proposes to them the combat of the Cestus, wherein he had made himself so redoubtable. He tells them, that they had to make a choice of the bravest amongst them, in order to put him up against him. Pollux, one of the Dioscuri accepts his insolent challenge. The poet gives us a very interesting description of this combat, in which the King of the Bebrycians is slain. The Bebrycians want to avenge his death and are routed.

The Sun was already lighting up the gates of Orient, and seemed to invite the shepherd and his flock to the pasture grounds, when the Argonauts, after having loaded their vessel with the booty, which they had made of the Bebrycians, re-embarked and set sail towards the Bosphorus. The Sea was getting high; the waves were engrossing like enormous mountains, threatening to engulf the vessel, but the art of the pilot averts the effect. After some dangers they land on the coast, where Phineus, famous on account of his misfortunes, reigned.

The poet narrates here the famous adventures of Phineus who had been struck with blindness, and who was persecuted by the Harpies. Apollo had granted him the art of divination. When the unhappy Phineus learnt the arrival of these travellers, he leaves his dwelling, directing and assuring his tottering steps with a staff. He speaks to them, as if he was already informed about the subject of their voyage, he draws a picture of his misfortunes, and implores their assistance against the ravenous birds, which give him so much trouble, and that it was reserved only to the sons of Boreus to exterminate them. Those sons of Boreus belonged to the party of heroes, who were on board of the vessel of Jason. One of the mi, Zethus, with tears in his eyes, takes the old man by the hand and speaks to him, trying to console him, by giving him the most flattering hopes. Accordingly a dinner was prepared for Phineus, which the Harpies as usual wanted to carry off. They begin soiling the tables, but it is for the last time, and in flying away, they leave an infectious stench behind. However they are pursued by the sons of Boreus sword in hand, and would have been killed, but for the intervention of the Gods, who dispatched Isis through the air, in order to prevent them from doing so. At all events the sons of Boreus exact from them the promise, of never again troubling the repose of Phineus, and they return afterwards on board of their vessel.

In the meantime the Argonauts prepare a dinner, to which they invite Phineus, and where he eats with the best appetite. Seated before his hearth, this old man traces for them the route, which they had to take, and points out to them the obstacles which they would have to surmount. As a soothsayer, he discloses to them. all the secrets, which it was possible for him to reveal, without displeasing the Gods, who had already punished him for his indiscretion. He informs them, that on leaving his states, they would have to pass through the Cyanaean, rocks, which are not approached without impunity. He gives them a short description of these rocks, and also useful advise how to escape the dangers. He recommends them to consult the dispositions of the Gods in their respect, by letting loose a dove. "He tells them, that if she should make the passage safely, not to hesitate a moment to follow her, and force this terrible passage by plying their oars steadily; because the efforts, which we make for our safety, are worth as much at least, as the prayers we address to the Gods. But should the bird perish, then return at once because that will be a proof, that the Gods are opposed to your passing through it." He traces afterwards a map of the whole coast, along which they would have to sail: he reveals to them chiefly the terrible secret of the dangers, to which Jason would be exposed on the shores of the Phasis, if he wanted to carry off the precious deposit, which was guarded by a terrible dragon, laying at the foot of the sacred beech tree, on which the golden fleece was suspended. The picture, which he draws of it, fills the Argonauts with apprehensions, but Jason bids the old man to proceed with his narration, and above all to tell him, whether they might flatter themselves to return in safety to Greece.

Old. Phineus answers, that he would find guides, who would conduct him where he wanted to go; that Venus would favour his enterprise, but that he was not allowed, to say more about it. He had just finished speaking, when the sons of Boreus returned, announcing that their chase of the Harpies was ended forever, and that they had been banished to Crete, whence they would never get out. These happy news fills the whole assembly with joy.

After having erected twelve altars to the twelve great Deities, the Argonauts re-embarked, taking with them a dove, which should serve them as a guide. Minerva, taking an interest in the success of their enterprise, had already stationed herself near those terrible rocks, in order to facilitate their passage. It will be observed here, that it is wisdom personified under the name of Minerva, who would make them avoid those dangerous rocks, which border these straits on all sides. Such was the language of ancient poetry.

The poet describes here the amazement and the terror of the Argonauts at the moment, when they approach these terrible rocks, in the midst of which the foaming surge is boiling. Their ears are stunned by the awful noise of these clashing rocks, and by the impeduous roar of the foaming surges breaking on the shore. The pilot Tiphys is manoeuvring with the helm, while the rowers assist him with all their might.

Euphemus had taken his stand on the prow of the vessel and lets the dove fly, the fight of which is followed by every eye: she flies through the rocks, which are hurled against each other, nevertheless without touching them. She looses merely the extremity of her tail. Meanwhile the raging billows make the vessel whirl about: the rowtrs shriek; but the pilot reproves and orders them to keep steady, and to ply the oars with all their might, in order to escape from the torrent, which carries them along; they are brought back by the waves into the midst of the rocks. Their terror is extreme and death seems suspended over their heads. The vessel, carried to the top of the waves, rises even higher than the rocks, only to be precipitated the next moment into the abyss of the waters. At that moment Minerva pushes the vessel with her right, while supporting herself with the left hand against one of the rocks, and makes it fly on the deep with the rapidity of an arrow; scarcely had it suffered the slightest damage.

The Goddess gratified of having saved the vessel, returns to the Olympus, and the rocks settle down, conformably with the dictates of Destiny. The Argonauts, being thus once more in the enjoyment of an open sea, thought that they had been, so to say, drawn out from. the abyss of Hell. On this occasion Tiphys makes a speech, in which he explains them all what they owed to the skill of their manoeuvres, or figuratively speaking, to the protection of Minerva, and tells them to remember, that it is the same Goddess, under whose direction their vessel had been constructed, which on that account was imperishable. The passage of the Cyanpean rocks was much dreaded by navigators; and it is still so up to this day. Much skill and prudence was wanted in order to make this passage. Here is the foundation of those frightful tales, which were repeated by all the poets. It was the same with the straits of Sicily. It is thus that poetry has sown everywhere the charm of the marvellous, and has covered Nature's phenomena with the veil of allegory.

Plying their oars without relaxation, the Argonauts had meanwhile already passed the mouth of the impetuous Rhebas; also that of Phyllis, where Phryxus had in olden times immolated his Ram. At twilight they arrive near a deserted island, called Thynias. where they effect a landing. There, Apollo appeared to them. That God had left Lycia, and proceeded towards the North, which happens at the passage of the Sun to the vernal equinox, or when the Sun is going to conquer the famous Ram of the constellations.

After having made a sacrifice to Apollo, the Argonauts quit the island and pass in sight of the mouth of the river Sagaris, Lycus, and of the lake Anthemuis. They arrive at the peninsula of Acherusia, which prolongs itself into the sea of Bithynia. There is a valley, where is to be found, in the midst of a forest, the cavern of Pluto and the mouth of. the Acheron.

They are favourably received by the King of the country, being an enemy of Amycus, the King of the Bebrycians, whom they had killed. This Prince and the Mariandynians his subjects, thought they saw in Pollux a beneficent Genius and a God. Lyeus, which was the name of this Prince, listens with pleasure to the narrative of their adventures; he orders all kinds of provisions to be brought on board of their vessel, and gives them his son, in order to accompany them in their expedition: Idmon the soothsayer and Tiphys the pilot, both died here. The latter is replaced by Ancteus, who takes the management of the vessel.

They re-embark and taking advantage of a favourable wind, the navigators arrive soon at the mouth of the river Callirhce, where Bacchus in olden timles, on his return from India, celebrated feasts, accompanied by dances. They made in this place, libations over the tomb of Sthenelaus, and afterwards re-embarked.

After several days the Argonauts arrive at Sinope, where they found some of the companions of Hercules, who had settled in that country. They double afterwards the Cape of the Amazons and pass in front of the Thermodon. They finally arrive near the island of Æetias, where they are attacked by formidable birds, which infested the island. They give them chase and put them to flight.

Here they found the sons of Phryxus, who had left Colchis for Greece, and who had been driven by shipwreck on this deserted island. These unfortunate men implore the assistance of Jason, to whom they make known their birth and the object of their voyage to Greece.

The Argonauts are overjoyed at their sight, and congratulate themselves with such a lucky accidental meeting. Really, they were nothing less than the grandsons of Aeetes, the owner of the rich fleece, and the sons of Phryxus, who had been carried on the back of the famous Ram. Jason makes himself known as their kinsman, being the grandson of Cretheus, the brother of Athamas their grandfather. He tells them, that he was on his way to see Metes, without however informing them of the object of his journey. However not long after that, he communicates it to them, inviting them at the same time to come on board of his vessel and to be his guides.

{p.194} The sons of Phryxus do not conceal from him the dangers of such an undertaking, and they make principally a frightful picture of that dragon, which sleeps neither day or night, watching the rich treasure, which they desire to carry off. This information fills the Argonauts with apprehensions, except brave Peleus, who vows vengeance against Æetes, if he should refuse their request. The sons of Phryxus are received on board, and the vessel, impelled by a favourable wind, arrives in a few days at the mouth of tile river Phasis, which traverses Colchis. They lower their sails, and with the aid of their oars they ascend the river. The son of Teson, while holding in his hand a golden cup, makes libations of wine to the waters of the Phasis, he invokes the Earth, the tutelar Divinities of Colchis, and the Manes of the heroes, who had formerly inhabited it. After this ceremony, Jason, encouraged by the advice of Argus one of the sons of Phryxus, orders to come to anchor, while waiting for the return of day. Here ends the second Canto.

CANTO III

So far everything has passed in preparations, which were necessary, in order to bring about the principal action of the poem. The treasure, which it was the purposes to conquer, was at the outermost confines of the East. It was necessary to arrive there, before making an attempt to obtain the precious fleece either by persuasion or artifice, or by force. The poet was therefore obliged to describe such a long voyage, with all the circumstances, which are supposed to have accompanied it. Thus Virgil makes his hero travel seven years; before he arrives at Latium, to form there the projected establishment, which is the sole object of the poem. It is only at the seventh book, that the principal action commences: on this account he invokes again Erato or the Muse, which shall obtain for his hero the hand of Lavinia, the daughter of the King of the Latins, where he wishes him to settle. Apollonius, after having conducted his hero to the shores of the Phasis, as Virgil conducts Eneas to those of the Tiber, invokes here likewise Erato or the Muse presiding over Love. He invites her to relate, how Jason succeeded to get finally possession of this rich fleece with the assistance of Medea, the daughter of Æetes, who fell in love with him. He first presents us with the spectacle of three Goddesses, Juno, Minerva and Venus, who take an interest in the success of the son of Aeson. The two first go to the palace of Venus, a description of which is given by the poet. Juno communicates to Venus her fears about the fate of Jason, whom she has taken under her protection against the perfidious Pelias, who had even insulted her. She makes the eulogy of Jason, with whom she is extremely well satisfied. Venus replies, that she is ready to do all that the spouse of the great Jupiter might request. Juno persuades Venus to request her son, of inspiring the daughter of Æetes with a passionate love for Jason, because it this hero could draw the young Princess into his interest, he would be sure to be successful in his enterprise. The Goddess of Cythera promises to induce her son to comply with the wishes of the two Goddesses, and without losing time, she goes in search of Cupid all over Olympus, and finds him in an orchard playing with young Ganymede, who had been recently admitted in the Heavens. His mother takes him by surprise and kisses him tenderly; she informs him at the same time of the wishes of the Goddesses, and explains the service, which is expected of him.

The child, seduced by the caresses of Venus and by her promises, quits his play, takes his quiver, laying at the foot of a tree, and arms himself with his, bow. He leaves the Heavens, by the gates of Olympus, traverses the air and descends to the Earth.

Meanwhile the Argonauts lay still concealed in the shade of thickets along the shore of the river. Jason makes to them an allocution. He communicates his projects, inviting all at the. same time, to give him the benefit of their opinions. He exhorts them, to stay on board, while he would be gone to the palace of Æetes, accompanied only by the sons of Phryxus and Chalciope, with two other companions. He tells them, that his plan is, to employ at first suavity of manners and solicitations in order to obtain from the King the famous fleece. He departs with the "caduceus" in his hand and proceeds to the city of Æetes, where le arrives at the palace of that Prince. The poet gives here a description of this magnificent edifice, near which two high towers are observable. One of them was inhabited by the King and his spouse; and the other by his son Absyrtus, whom the Colchians called Phieton. It will be observed here, that Phaeton is the name of the celestial Charioteer, placed on tie equinoctial point of spring, and who experienced the tragic fate of Absyrtus, under the names of Phaeton, Myrtilus, Hyppolyte, &c.; he follows Perseus and Medusa in the Heavens.

In the other apartments resided Chalciope, the wife of Phryxus and mother of the two new companions of Jason, and her sister Medea. The latter performed the office of priestess of Hecate, who, according to traditions, had Perseus for father. Chalciope, when perceiving her sons, runs to meet them and receives them with open arms. Medea utters a cry at the sight of the Argonauts. Æetes, accompanied by his wife leaves the palace. The whole court is agitated. Meanwhile Love, without being observed, had traversed the air: he stopped under the vestibule, in order to bend his bow; then he stepped over the threshold of the door and hid himself behind Jason. Thence he shoots an arrow into the heart of Medea, who stands there mute and perplexed. Soon the fire is lighted in her heart and makes progress burning in all her veins; her eyes sparkle with a vivid flame and are fixed on Jason. Her heart utters a sigh: a light flutter agitates her bosom; her respiration is quick; paleness and blushes succeed each other on her cheeks. The poet goes then on to narrate the reception, which Æetes gives to his grandsons, whose unexpected return surprises him. He reminds the sons of Phryxus the advice, which he had given them before their departure, in order to dissuade them from an enterprise, of the dangers of which they were well aware. He interrogates them about the strangers, who accompany him. Argus, answering in the name of both, gives a description of the storm, which had driven them on a deserted island, consecrated to Mars, from which they had been rescued solely by the succour of these navigators. At the same time he reveals to his grandfather the object of their voyage, and the terrible orders of Pelias. He is not concealing the lively interest, which Minerva takes in the success of this enterprise: she it was, who had supervised the construction of their vessel, the superiority of. which he extols, and on board of which the flower of the heroes of Greece had embarked. He introduces to him Jason, who with his companions comes to request the famous fleece.

This address renders the King furious: he is filled with indignation against the sons of Phryxus, that they could take upon themselves, to deliver such a message. As he was thus flying into passion, and menacing his grandsons as well as the Argonauts, the fiery Telamon wished to answer him in the same violent strain. But Jason checks him, and in a modest and smooth tone of voice explained to the King the motives of his voyage, with which ambition had nothing whatever to do, and which he had undertaken solely in obedience to the commands of Pelias. He promises, that should he extend to them his favours, he would on his return to Greece, publish his glory, and even give him assistance in his wars, which he might be engaged in with the Sarmatians and other neighbouring nations.

Æetes was at first doubtful, which side he should take, respecting them, but finally resolves upon promising them, what they ask for, but under one condition, which he imposes, and the execution of which would be a sure test of their courage. He tells Jason, that he has two Bulls with feet of brass, and blowing fire from their nostrils; that he would put them to a plough, and plough up a field, consecrated to Mars, and that instead of wheat he would sow there serpents' teeth, from which suddenly warriors would rise; that he would then reap them with the point of his lance, and that all this would be executed between sunrise and sunset. He proposes to Jason to do all this likewise and promises him, that should he be successful, he would hand him over the rich deposit, which he demands. Without that there was no hope for him; because, says he, it would be unworthy of myself, to give up such a treasure to one less courageous than myself.

At this proposition Jason remains dumbfounded, not knowing what to answer, so daring seems to him this undertaking. Notwithstanding he concludes finally to accept the condition.

The Argonauts leave the palace, followed by Argus alone, who makes signs to his brothers to remain. Medea, who had perceived them, remarks above all Jason, distinguished from the rest of his companions by his youth and gracefulness. Chalciope, fearing to displease her father, retires with her children to her apartments, while her sister still follows with her eyes the hero, whose form had seduced her. When she had lost sight of him, his image remains still engraved in her memory. His speeches, his gestures, his gait and principally his reckless air, are ever present to her agitated mind. She is afraid, lest he should lose his life; she already fancies, that he would be the victim of such a dating enterprise. Tears escape her beautiful eyes; she complains bitterly about it and her best wishes for the success of this young hero accompany him. She invokes for him the succour of the Goddess, of which she is the priestess.

The Argonauts traverse the city and take the same route, which they had followed when coming. Argus then addresses Jason, reminding him again of the magical art of Medea and that it would be of the utmost importance to draw her into his interest. He offers to take the necessary steps in regard to it, and to sound the dispositions of his mother. Jason thanks him for his proposals, which he accepts; he returns then to his vessel. His sight fills them with joy, soon to be followed by dejection, when he informs his companions of the conditions, which had been imposed upon him. Argus however tries to calm their apprehensions. He speaks to them of Medea and of her magic art, of which he narrates its wonderful effects. He takes it upon himself to obtain her assistance.

Jason, after consultation with his companions, sends Argus to the palace of his mother, while the Argonauts effect a landing on the shores of the river, where they make preparations for a fight if necessary.

Æetes meanwhile has assembled his Colchidians, in order to contrive some treacherous project against Jason and his warriors, whom he represents to his subjects as a horde of robbers, who came to spread over their country. He orders therefore his soldiers to go and attack the Argonauts, and to burn their vessel.

As soon as Argus had arrived at the apartment of his mother, he requests her to solicit the assistance of Medea in favour of Jason and his companions. The latter had already, of her own accord, taken an interest in the fate of those heroes, but she was afraid of the wrath of her father. A dream which she had and of which the poet gives a detailed account, compels her to break silence. She has already made a few steps, in order to visit her sister, when all at once she returns to her apartment, where she throws herself upon her bed, abandoning herself to the utmost grief and uttering protracted groans. Chalciope, having heard of it, flies immediately to the assistance of her sister. She finds her bathed in tears and in her despair bruising her face. She asks her for the. motives of her violent agitation; and supposing it to be the effect of the repro blches of her father, of which she complains herself, she declares her desire to escape with her children far from this palace.

Medea blushes and is ashamed at first to answer; filially she breaks silence, and giving way to the dominion of love, which subjugates her, she expresses her fears about the fate of the sons of Phryxus, which her grandfather Æetes menaces with death, together with those strangers. She discloses to her the dream, which seems to presage this misfortune. Medea made those remarks, in order to sound the disposition of her sister and to see, whether she would not request her to assist her son. And actually Chalciope opens her heart to her; but before confiding her her secret, makes her take an oath, that she would keep it faithfully, and would do all, which should depend on her, in order to serve and protect her children. Speaking these words and melting in tears, she presses the knees of Medea in the attitude of a suppliant. The poet draws here a picture of the grief of both these Princesses. Medea loudly attests by all the Gods, that she is disposed to do all what her sister would ask her to do. Chalciope ventures then to speak of those strangers and particularly of Jason, in whom her children had taken so lively an interest. She confesses that her son Argus came to induce her, to solicit for them the assistance of Medea in this perilous enterprise. At these words the heart of Medea is in raptures: her beautiful face is coloured with a modest blush. She consents to do for them all, which would be asked for by a sister, to whom she has nothing to refuse, and who had been almost a mother to her. She recommends her the profoundest secrecy. She tells her, that at the break of day she would have the necessary drugs be brought into the temple of Æceate, in order to make the terrible Bulls drowsy. Chalciope leaves her in order to inform her son of the promises of her sister. Medea, being thus left alone in her apartment, gave herself up in the interval to those reflections, which were the natural consequences of such a project.

It was already late, and Night was spreading her gloomy veil over the earth and the sea. A profound silence reigned in all Nature. The heart of Medea alone was not quiet, and sleep did not close her eyelids. Uneasy about the fate of Jason, she dreaded on his account those terrible bulls, which he had to put to the plough, and. with which hoe was obliged to plough the field consecrated to Mars.

These fears and these emotions are well described by the poet, who employs about the same comparisons as Virgil does, when he depicts the perplexity of either Aeneas or Dido. He lets the young Princess hold a soliloquy, which gives us a picture of the anxiety agitating her soul, and the irresolutions of her mind. She holds on her knees the precious box, containing her magical treasure; she is bathing it with her tears, whilst assailed with the gloomiest reflections. She awaits the return of Aurora, which finally arrives and is driving away the shades of Night. Meanwhile Argus had left his brothers in order to await the fleet of the promises of Medea, and had returned to the ship.

Daylight had again returned, and the young Princess, occupied with the cares of her toilet, had somewhat forgotten her sorrows. She had repaired the disorder of her hair, perfumed her person with essences, and had attached a white veil to her head dress. She gives orders to her maids, twelve in number and all virgins, to put the mules into harness, which had to draw her chariot to the temple of Hecate. During the interval she employs the time with preparing the poison, which she had extracted from the simples of the Caucasus, grown from the blood of Prometheus. She mixes therewith a blackish liquor, which had been thrown up by the eagle, which had picked the liver of that famous criminal. She rubs with it the girdle, which encircles her bosom. She mounts her chariot with two maidens, one on each side, and she traverses the city, holding the reins and the whip, in order to guide the mules. Her maidens follow her, forming a cortege like that of the Nymphs of Diana, when they are ranged around the chariot of that Goddess.

The walls of the city are soon passed. When drawing near the temple, she descended from the chariot. She communicated her project to her maidens, exacting at the same time the greatest secrecy, she bids them to pluck flowers and orders them to retire, as soon as they would see the stranger make his appearance, whose plans she wishes to support.

Meanwhile the son of Æson, guided by Argus and accompanied by the soothsayer Mopsus proceeds towards the temple, where he knows that Medea would go at the break of day, Juno herself had taken care to make her charming, and by surrounding her with a shining light. The success of his undertaking is already announced by happy omens, interpreted by Mopsus. He advices Jason to see Medea alone and to converse with her, while he and Argus would wait for him. Medea in her impatience to see the hero arrive, turned her restless looks in that direction, whence Jason had to come. Finally he appears before her, like the luminary, which announces the heat of summer at the moment, when it emerges from the bosom of the waves. Here the poet gives us a description of the impression, which that sight produced on the Princess. Her eyes are clouded, her cheeks are blushing, her knees tremble, and her maidens, witness of her embarrassment, have already retired. The two lovers remain for some time dumb and confounded in each others presence. Finally Jason, being the first to find words, tries to reassure her alarmed modesty, and begs her to open her heart to him, particularly in a place, imposing on him a religious respect for her.

He tells her, that he is already informed of her good intentions in his behalf, and of the assistance which she was kind enough to promise him. He entreats her in the name of Hecate, and of Jupiter, who protects strangers and supplicants, to interest herself in the fate of a man, who appears before her in this double quality. He assures her before hand of his entire gratitude and that of his companions, who would publish the glory of her name throughout Greece. He adds, that she alone could fulfil the wishes of their mothers and wives, who expect them, and whose eyes are fixed upon the sea, whence they had to return to their country. He mentions the example of Airadne, who interested herself in the success of Theseus, and who, after having secured the victory of that hero, embarked herself with him and left her country. In acknowledgement of this service, continued Jason, her crown has been placed in the Heavens. The glory, which awaits you, shall not be inferior, if you restore this band of heroes to the wish of Greece.

Medea, who had listened to him with down cast eyes, smiles sweetly at these words; she looks at him and wishes to answer him, without knowing where to commence her speech; her thoughts come on and confound themselves: she draws from her girdle the powerful drug, which she had concealed there. Jason takes it with extreme satisfaction: she would have given him her whole soul, if he had asked for it, so much was she smitten with the beauty of this young hero, of whom the poet has drawn here a most charming picture. Both alternately cast their eyes down or are looking at each other. Finally Medea finds, words in order to give him useful advice, which would secure him the success of his enterprise; she recommends him, that after receiving from her father Aeetes the dragon's teeth, which he should sow into the furrows, to wait the precise hour of midnight, in order to make himself alone a sacrifice, after having washed himself in the river.

She prescribes all the requisite ceremonies, in order to render' this sacrifice agreeable to the awful Goddess: She instructs him how to use the drug, which she had given him, and with which he had to rub his weapons and his body in order to become invulnerable; she points out to him the means to destroy the warriors, which should grow from the teeth, which he should sow. Thus, adds Medea, you shall succeed to carry off the rich fleece and to bring it to Greece, if it is really true, that it is your intention to incur again the dangers of the sea. While the Princess utters these words, tears are flowing down her cheeks, at the idea of a separation from this hero, should he carry out his project of returning to distant regions. Casting down her eyes she remains silent for a short time; then she takes his hand, which she presses while saying: At least, when you shall have returned to your country, you will remember Medea, the same as she shall remember Jason, and tell me, before you part, where you intent to go. Jason moved by her tears, and pierced already by the arrows of Love, swears to her, that he shall never forget her, in case he should have the good fortune to arrive in Greece and that Agetes should not suscitcate new obstacles. He ends by giving her some details about Thessaly, and speaks of Ariadne, in answer to some enquiries of Medea about her; he manifests his desire of being as fortunate as Theseus was. He invites her to accompany him to Greece, where she would enjoy add the consideration, which she merited; he makes her the offer of his hand, and swears to her eternal faithfulness.

This speech of Jason flatters and soothes the heart of Medea, even when she could not dissemble the misfortunes, with which she was menaced, if she should resolve to follow him.

Meanwhile she is expected by her maidens with impatience, and the hour had arrived, when the Princess had to return to her mother's palace: she did not perceive the moments, which flooded away by far more rapidly than she desired, had not Jason prudently advised her to retire, before night should surprise them, and that somebody might. suspect her meeting.

They make an appointment for some other time, and they separate. Jason returns to his ship, and Medea rejoins her maidens, which she does not notice, so much was her mind occupied with other ideas: she remounts again the chariot and returns to the Kings palace. She is questioned by her sister Chalciope about the fate of her children, she hears nothing and answers nothing; she sits down on a chair near the bed, and there immersed in the profoundest grief, she resigns herself to the gloomiest reflections.

Jason on his return on board, informs his companions of the success of his interview, and shows them the powerful antidote, with which he is provided. The night passes, and the next morning at daybreak the Argonauts send to the King, in order to demand the dragon's teeth. They are handed over to them, and they give them to Jason, who on this occasion plays absolutely the part of Cadmus. This confirms the identity of these two heroes, whose name is that of the Serpentarius, or of the constellation, which rises in the evening, when the Sun enters the sign of the Bull, and the Ram with the golden fleece precedes its chariot. Meanwhile the brilliant Star of Day had. dived into the bosom of the waves and Night had put her black coursers to her chariot. The sky was serene and the air was calm. In the silence of the night Jason offers a sacrifice to the Goddess, who there presides. Hecate hears him with favour and appears to him under the form of a terrible spectre. Jason is astonished but not discouraged, and soon after rejoins his companions.

The summits of Causasus, whitened with eternal snow were now shown by Aurora. King Æetes, invested with the formidable armour, which had been given to him by the God of battles, was now preparing to depart for the field of wars. His head was covered with a helmet, the dazzling splendour of which offered the image of the disk of the Sun at the moment, when it rises from the bosom of Thetis. Before him he held an enormous shield, formed of several hides, and in his hand he balanced such a formidable spear, that none of the Argonauts could have resisted it, except Hercules; but that hero was no more with them. At his side was his son Phaeton; he held the coursers, which had been put to the chariot, to be mounted by his father. He now takes the reins, and advances through the city, followed by a multitude of people.

Jason on his part, following the counsel given him by Medea, rubs his weapons with the drug received from her, which was to strengthen their temper. He rubs also his body with it, which acquires new vigour and a force, which nothing could resist. He wields proudly his weapons, displaying his muscular arms. He proceeds to the field of Mars, where Æetes and his Colchians are already waiting for him. Jason was the first to leap from his vessel, all accoutred and armed, ready for the combat: he might have been taken for the God Mars himself. With complete self-possession he takes a view of the field, which he has to plough; he sees the brazen yoke, to which he must put the terrible bulls, and the rough ploughshare, with which he has to plough the field. He approaches, and thrusts his lance into the ground; he fixes his helmet and advances merely armed with his shield, in order to look for the bulls with the fiery breath They rush at once out from their gloomy den, covered by a dense smoke. Fire is darting from their large nostrils with an impetuous noise. The Argonauts are frightened at that sight, but the intrepid Jason holds his shield before him and awaits them with firmness, like an immovable rock would present its sides to the foaming wave. The impetuous bulls make a thrust at him with their horns, without being able to make him stagger. The air resounds with their awful lowing. The flames gushing out from their nostrils, resemble to that vortex of fire, which a fiery furnace is blazing out, and which successfully enters and breaks out again with renewed violence. Very soon is the activity of the flame weakened by the magical force of the drug, with which the body of the hero had been rubbed. The invulnerable Jason takes one of the bulls by the horns and with his brawny arm puts it under the yoke, while throwing it down; he does the same with the other, and thus he conquers them both.

Such is Theseus or the Sun under another name, who on the field of Marathon overcomes that same Bull, which was placed afterwards in the Heavens, and which figures here in the fable of Jason, or of the conquering star of winter, triumphing over the equinoctial Bull. This is that Bull which has been subjugated also by Mithras.

Æetes remains confounded at the sight of such an unexpected victory. Already is Jason, after having put the bulls to the yoke, driving them on with the point of his lance; and making the plough go ahead: he has already ploughed up several furrows notwithstanding the hardness of the ground, which scarcely yields to the plough and breaks up with noise. He sows the dragon's teeth, unyokes the bulls and returns to his vessel. But Giants, which had sprung from the furrows, which he had ploughed, covered the field all armed. As soon as Jason had returned, he attacked them, and throws an enormous rock in the midst of their serried ranks; many are crushed by it; others kill each other, while contending among themselves about the rock, which had been thrown amongst them. Jason takes advantage of their disorder in order to charge them sword in hand, and the steel of the hero makes an ample harvest of them. They fall one above the other, and the earth, which had brought them forth, receives their corpses in her bosom. Æetes. remains spellbound and is grieved by this spectacle. He returns to the city lost in meditation and planning new snares for the ruin of Jason and his companions. The setting in of Night ends this combat.

CANTO IV

Æetes is uneasy and suspects his daughters, of combining with the Argonauts. Medea perceives it, and is alarmed on that account. In her despair she was going to the last extremities, when Juno suggests her the plan to escape with the sons of Phryxus. She is re-animated by this idea. Hiding in her bosom the treasures contained in her magic box and the mighty herbs, she kisses her bed and the doors of her apartment and cutting off a ringlet of her hair, leaves it as a remembrance to her mother. She gives utterance to her profound grief and addresses to all a last and sad farewell. Shedding floods of tears, she escapes furtively from the palace, the gates of which open by her enchantments. She was barefoot; with her left-hand she supported the extremity of a light veil falling from her forehead, while she lifted up the folds of her dress with her right. Medea traverses thus the city with nimble foot, by taking by-streets, and is soon outside the city walls, without being discovered by the sentinels. She continues her flight in the direction of the temple, the roads of which she is well acquainted with, having often been in the habit of gathering herbs, growing among the tombs in its neighbourhood. Her heart beats quicker for fear of a surprise. The Moon, which looks down upon her, remembers her love with Endymion, of which that of Medea and Jason appears to her to be the image. On that occasion, the poet makes that Goddess address Medea, while she is fleeing across the plain, into the arms of her lover. Her steps are along the shores of the river in the direction of the camp-fires of the Argonauts. Her voice is heard amidst the shades of Night. She calls for Phrontis, the youngest of the sons of Phryxus, who recognizes instantly with his brothers and Jason, the voice of the Princess: the rest of the Argonauts are surprised. She calls thrice, and thrice she is answered by Phrontis. The Argonauts row towards the shore, on which her lover is the first to leap, in order to receive her. He is quickly followed by the two sons of Phryxus, Phrontis and Argus. Medea falls on her knees exclaiming: friends, save me, save yourselves, we are lost, all is discovered. Let us quickly go on board, before the king has harnessed his coursers. I shall deliver into your hands the fleece, after having put to sleep the terrible Dragon, which keeps watch. over it. And thou, O Jason, remember the oaths, which thou has made to me; and if I leave my country and my parents, that you will take care of my reputation and of my honour. Thou hast promised it to me, and the Gods are my witnesses.

Medea's address showed heartfelt grief: Jason at the contrary rejoiced, and his heart was filled with gladness. He raises her from her kneeling position, he embraces her tenderly, and restores her courage. He calls the Gods, Jupiter and Juno to witness his oath, to make her his wife at the instant when he should return to his country. At the same time he takes her by the hand in sign of their union. Medea advises the Argonauts, to push their vessel quickly onward to the sacred grove, where the precious fleece lay concealed in order to carry it off under cover of the night, and unknown to Æetes. Her commands are executed and she goes herself on board the vessel, which has already distanced the shore. The wave foams rustling under the edge of the oar. Once more Medea turns her looks towards the land, and extends to it her arms. Jason consoles her by his exhortations and raises again her courage. It was at that moment of the night, which precedes the return of Aurora, of which the hunter takes advantage. Jason and Medea land in a meadow, where formerly rested the Ram, which carried Phryxus to Colchis. They perceive the altar, raised by the son of Athamas, and on which he had made a sacrifice of this Ram to Jupiter. The two lovers proceed alone to the wood, in order to find the sacred beech tree, on which the fleece was suspended. At the foot of the tree they perceived an enormous Dragon already unrolling its tortuous folds, ready to pounce upon them, and the horrible hisses of which carry terror far and near. The young Princess advances towards it, after having invoked the God of Sleep and the dreadful Hecate. Jason follows her although seized with fear. Already overcome by the enchantments of Medea, the monster stretched out on the ground the thousand folds of his immense body: nevertheless his head was still raised, menacing our hero and the Princess. Medea shakes over his eyes a branch steeped in a soporific water. The Dragon thus made drowsy, drops down and falls asleep. Jason immediately seizes the fleece and carrying it off, returns with it and with Medea quickly on board the vessel, where he was expected. Already has he cut with his sword the cable, which fastened it to the shore and taken his place near the pilot Ancaeus along with Medea, while the vessel, propelled by vigorous pulls of the oars, strives to gain the high sea.

Meanwhile the Colchians headed by their King, were hurrying in crowds to the shore, which they made re-echo with threatening shouts; but the ship Argo was already rowing in the open sea. In his despair the King invokes the vengeance of the Gods, and gives orders to his subjects to pursue the foreigners, who had robbed the precious deposit and had ravished his daughter. His orders are obeyed; they embark, and go in pursuit of the Argonauts.

The latter propelled by a favourable wind, arrive at the end of three days at the mouth of the river Halys. They land on the coast, and by the advice of Medea they offer a sacrifice to Hecate. There they hold council, in order to decide on the route, which they had to take in returning to their country. They resolve to gain the mouth of the Danube and to ascend that river.

During that time their enemies had divided into two parties: one of which had taken the way of the straits and of the Cyanmean rocks, while the other was taking also the route of the Danube. Absyrtus or Phaeton, the brother of Medea, was at the head of the latter. The Colchians enter by one pass of the river; the Argonauts by the other. They land on an island consecrated to Diana, and there they deliberated, whether they should not make a compromise with their enemies, by consenting to give up Medea, provided they should be permitted to carry off the Golden fleece. It is here that Absyrtus perished by the hand of Jason, drawn into a snare, which had been laid for him by his sister. The Colchians without a leader are soon defeated. Escaped from this danger, the Argonauts ascended the river and reach Illyricum and afterwards the sources of the Eridanus. Then they enter the Mediterranean Sea, and sailing along the coast of Etruria, they land on the island of Circe, daughter of the Sun, in order to be purified of the murder of Absyrtus: thence they sailed before the wind towards Sicily. They perceive the isles of the Sirens and the rocks of Charybdis and of Scylla, from which they escape. Finally they arrive at the island of Pheacia, where Alcinous reigned, who received them favourably. Their happiness is however soon disturbed by the arrival of the fleet of the Colchians. which had pursued them by the way of the Bosphorus. Alcinous saves them from this new danger, and Jason marries Medea in that island. At the end of seven days, the Argonauts re-embark; they are however thrown by a violent storm on the coasts of Lybia, in the vicinity of the redoubtable Syrtes; they traverse the sands, carrying their vessel on their shoulders during twelve days; they arrive at the garden of the Hesperides, and launching into the Sea again, they land at night time at Crete; afterwards they reach the island of Ægina and finally the port of Pagasus, whence they had set out on their voyage.

We have abridged the narrative of their return, as well as their voyage, because both are merely the accessory parts of the poem, the sole action of which is the conquest of the golden fleece, after the defeat of the Bulls and of the terrible Dragon. That is the really astronomical part and as it were the centre, in which all the other fictions of the poem come to end. The poet had to sing an important epoch of the solar revolution, that in which the Star of Day, the conqueror of Winter and of Darkness, brought on by the polar Dragon, arrives at the celestial sign of the Bull, and brings Spring along in the train of its chariot, which is preceded by the celestial Ram, or the sign preceding the Bull.

This happened every year in March, at the rise in the evening of the Serpentarius Jason, and at the rising in the morning of Medusa and of Phæton, the son of the Sun. It was in the East, that the people of Greece saw the famous Ram arise, which seemed to be born in the climates, where they located Colchis, or in other words at the eastern extremity of the Black Sea. In the evening they perceived in the same places the Serpentarius, who in the morning at the rising of the Ram', was seemingly descending into the waves of the western Seas. This is the simple canvass, on which this whole fable had been embroidered. It is this singular phenomenon, which furnishes the matter for those poems, which were called by the Ancients: Argonautics, or the expedition of Jason and the Argonauts. The great navigator is the Sun: his vessel is also a constellation, and the Ram, which he is going to conquer, is likewise one of the twelve signs, namely the one, which in those remote ages, announced the happy return of Spring.

We shall very soon meet again with the same Dragon at the foot of a tree, bearing apples, which cannot be gathered with out rendering unhappy those, who had the imprudence to pluck them. We shall also see the same Ram under the name of Lamb, to be the object of veneration of the Initiates, who under its auspices, enter the Holy City, where the gold shines on all sides, and all that, after the defeat of the redoubtable Dragon. Finally we are going to see Jesus, conqueror of the Dragon, attired with the spoils of the Lamb or of the Ram, re-conduct his faithful companions to the celestial land, like Jason: this is, what is shown, under other names, by the fables of Eve and of the Serpent, by that of the triumph of Christ Lamb over the ancient Dragon, and by that of the Apocalypse. The astronomical foundation and the epoch of the time are absolutely the same.

Source: The Origin of All Religious Worship, translated from the French of Dupuis (New Orleans, 1872).

Photo credit: Library of Congress.