THE FLEECE AS GOLD MINING

AND OTHER COLCHIAN WEALTH

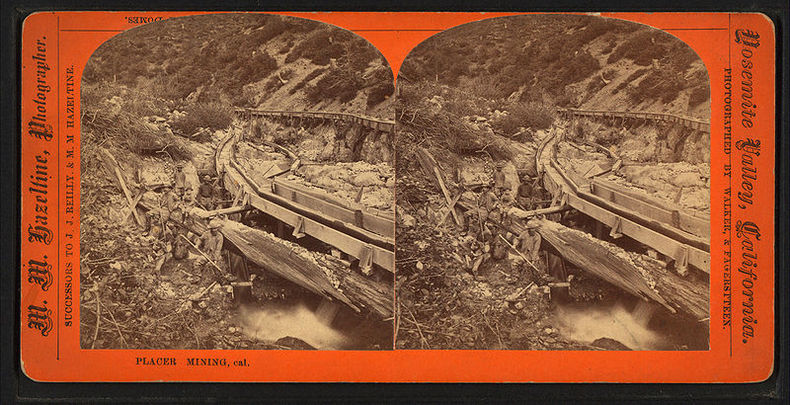

Gold Mining

The most persistent of all the theories of the origin of the Golden Fleece is that it was a literal or symbolic representation of gold mining operations on the Black Sea coast. While many mythologists preferred symbolic explanations, rationalized explanations like this one appealed to archaeologist, geologists, and other scientists who dealt with artifacts because it reinforced their preconception of myth as a reflection of material culture. From the theory's origin with Strabo in ancient times down to 21st-century attempts to electro-analyze Mycenaean gold for traces of Colchian molecules, this theory is the most frequently cited as the explanation for the Argonauts' journey. Below are three excerpts discussing the Argonauts and the gold of Colchis. Following these, we will discuss the broader theory of Colchian wealth as the foundation of the myth of the Golden Fleece.

THE GEOGRAPHY

Strabo

1st c. BCE- 1st c. CE

1.2.39. Æetes is generally believed to have reigned in Colchis, the name is still common throughout the country, tales of the sorceress Medea are yet abroad, and the riches of the country in gold, silver, and iron, proclaim the motive of Jason’s expedition, as well as of that which Phrixus had formerly undertaken.

11.2.19. In their country the winter torrents are said to bring down even gold, which the Barbarians collect in troughs pierced with holes, and lined with fleeces; and hence the fable of the golden fleece.

Source: Strabo, The Geography of Strabo, trans. Horace Leonard Jones (London: William Heinemann, 1918).

Strabo

1st c. BCE- 1st c. CE

1.2.39. Æetes is generally believed to have reigned in Colchis, the name is still common throughout the country, tales of the sorceress Medea are yet abroad, and the riches of the country in gold, silver, and iron, proclaim the motive of Jason’s expedition, as well as of that which Phrixus had formerly undertaken.

11.2.19. In their country the winter torrents are said to bring down even gold, which the Barbarians collect in troughs pierced with holes, and lined with fleeces; and hence the fable of the golden fleece.

Source: Strabo, The Geography of Strabo, trans. Horace Leonard Jones (London: William Heinemann, 1918).

THE DECLINE AND FALL OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE (vol. IV)

Edward Gibbon

1788

The waters, impregnated with particles of gold, are carefully strained through sheep-skins or fleeces, but this expedient, the groundwork perhaps of a marvellous fable, affords a faint image of the wealth extracted from a virgin earth by the power and industry of ancient kings. Their silver palaces and golden chambers surpass our belief; but the fame of their riches is said to have excited the enterprising avarice of the Argonauts.

Source: Edward Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, ed. J. B. Bury, vol. IV (London: Methuen & Co., 1901), 372.

Edward Gibbon

1788

The waters, impregnated with particles of gold, are carefully strained through sheep-skins or fleeces, but this expedient, the groundwork perhaps of a marvellous fable, affords a faint image of the wealth extracted from a virgin earth by the power and industry of ancient kings. Their silver palaces and golden chambers surpass our belief; but the fame of their riches is said to have excited the enterprising avarice of the Argonauts.

Source: Edward Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, ed. J. B. Bury, vol. IV (London: Methuen & Co., 1901), 372.

MINING: THE GREAT ADVENTURE

T. A. Rickard

1917

The fable may be interpreted thus: The sacred ram, the fleece of which Jason sought, refers to the Tibareni, or sons of Tubal, whose name means 'hammer,' for Tubal was a smith—the first of a noble and numerous family. The Tibareni were a tribe that mined for gold near the northern shore of Asia Minor. They washed the gravel of the gold-bearing stream into sluice-boxes on the bottoms of which they placed sheep-skins to arrest the fine gold. When the time came to clean-up, they removed the sheep-skins, shook out the coarser particles of metal, and hung the fleece to dry, so that the fine gold might be beaten out of it and saved. Thus the Greek mariners heard of the land in which golden fleeces hung on trees in a sacred grove by the Euxine. Jason is the type of youth, the seeker who goes forth with his comrades across the sea on the miner's quest. He finds that he must perform prodigies of labor before he can win the precious metal. In winning it he is aided by the sorceress Science, the modern Medea, who shows him how to use the fleece for arresting the fine gold in the bed of the stream Colchis, and even explains to him that the natural grease on the wool serves to promote the adhesion of the particles of gold. Placer mining, the aid of science to industry, and even flotation, are typified in the story of the Argonauts.

Source: T. A. Rickard, "Mining: The Great Adventure," Mining and Scientific Press, June 16, 1917, 831.

T. A. Rickard

1917

The fable may be interpreted thus: The sacred ram, the fleece of which Jason sought, refers to the Tibareni, or sons of Tubal, whose name means 'hammer,' for Tubal was a smith—the first of a noble and numerous family. The Tibareni were a tribe that mined for gold near the northern shore of Asia Minor. They washed the gravel of the gold-bearing stream into sluice-boxes on the bottoms of which they placed sheep-skins to arrest the fine gold. When the time came to clean-up, they removed the sheep-skins, shook out the coarser particles of metal, and hung the fleece to dry, so that the fine gold might be beaten out of it and saved. Thus the Greek mariners heard of the land in which golden fleeces hung on trees in a sacred grove by the Euxine. Jason is the type of youth, the seeker who goes forth with his comrades across the sea on the miner's quest. He finds that he must perform prodigies of labor before he can win the precious metal. In winning it he is aided by the sorceress Science, the modern Medea, who shows him how to use the fleece for arresting the fine gold in the bed of the stream Colchis, and even explains to him that the natural grease on the wool serves to promote the adhesion of the particles of gold. Placer mining, the aid of science to industry, and even flotation, are typified in the story of the Argonauts.

Source: T. A. Rickard, "Mining: The Great Adventure," Mining and Scientific Press, June 16, 1917, 831.

The Wealth of Colchis

The theories of the Golden Fleece as symbolic of Colchian gold were not confined solely to representations of actual gold mining. Other theorists saw in the Fleece a symbol of the broader wealth of Colchis, famed since antiquity for its precious metals. This theory originates primarily in Strabo's account, quoted above, and Pliny's description of the wealth of Colchis long after Jason's voyage.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 33.15

Before this time too, Saulaces, the descendant of Æëtes, had reigned in Colchis, who, on finding a tract of virgin earth, in the country of the Suani, extracted from it a large amount of gold and silver, it is said, and whose kingdom besides, had been famed for the possession of the Golden Fleece. The golden arches, too, of his palace, we find spoken of, the silver supports and columns, and pilasters, all of which he had come into possession of on the conquest of Sesostris, king of Egypt; a monarch so haughty, that every year, it is said, it was his practice to select one of his vassal kings by lot, and yoking him to his car, celebrate his triumph afresh.

Source: Pliny, The Natural History of Pliny, vol. 6, trans. John Bostock and H. T. Riley (London: George Bell and Sons, 1898), 93-94.

Before this time too, Saulaces, the descendant of Æëtes, had reigned in Colchis, who, on finding a tract of virgin earth, in the country of the Suani, extracted from it a large amount of gold and silver, it is said, and whose kingdom besides, had been famed for the possession of the Golden Fleece. The golden arches, too, of his palace, we find spoken of, the silver supports and columns, and pilasters, all of which he had come into possession of on the conquest of Sesostris, king of Egypt; a monarch so haughty, that every year, it is said, it was his practice to select one of his vassal kings by lot, and yoking him to his car, celebrate his triumph afresh.

Source: Pliny, The Natural History of Pliny, vol. 6, trans. John Bostock and H. T. Riley (London: George Bell and Sons, 1898), 93-94.

Thus, in William Stevenson's 1824 history of navigation and commerce, we find the following:

Having rendered it probable, from general considerations, that the object [of the Argonauts' mission] was the obtaining of the precious metals, we shall next proceed to strengthen this opinion, by showing that they were the produce of the country near the Black Sea. The gold mines to the south of Trebizond, which are still worked with sufficient profit, were a subject of national dispute between Justinian and Chozroes; and, as Gibbon remarks, "it is not unreasonable to believe that a vein of precious metal may be equally diffused through the circle of the hills." On what account these mines were shadowed out under the appellation of a Golden Fleece, it is not easy to explain. Pliny, and some other writers, suppose that the rivers impregnated with particles of gold were carefully strained through sheeps-skins, or fleeces; but these are not the materials that would be used for such a purpose: it is more probable that, if fleeces were used, they were set across some of the narrow parts of the streams, in order to stop and collect the particles of gold.

Source: William Stevenson, Historical Sketch of the Progress of Discovery, Navigation, and Commerce (Edinburgh: William Blackwood, 1824), 27.

Having rendered it probable, from general considerations, that the object [of the Argonauts' mission] was the obtaining of the precious metals, we shall next proceed to strengthen this opinion, by showing that they were the produce of the country near the Black Sea. The gold mines to the south of Trebizond, which are still worked with sufficient profit, were a subject of national dispute between Justinian and Chozroes; and, as Gibbon remarks, "it is not unreasonable to believe that a vein of precious metal may be equally diffused through the circle of the hills." On what account these mines were shadowed out under the appellation of a Golden Fleece, it is not easy to explain. Pliny, and some other writers, suppose that the rivers impregnated with particles of gold were carefully strained through sheeps-skins, or fleeces; but these are not the materials that would be used for such a purpose: it is more probable that, if fleeces were used, they were set across some of the narrow parts of the streams, in order to stop and collect the particles of gold.

Source: William Stevenson, Historical Sketch of the Progress of Discovery, Navigation, and Commerce (Edinburgh: William Blackwood, 1824), 27.

And again in a 1980 illustrated encyclopedia of mythology:

The Golden Fleece itself is a symbol of the fabulous wealth of the Caucasus region, which the Greeks exploited by settling colonies there, from the 7th century BC onwards.

Source: Richard Cavendish and Trevor Oswald Ling, Mythology: An Illustrated Encyclopedia (Rizzoli, 1980), 202.

The Golden Fleece itself is a symbol of the fabulous wealth of the Caucasus region, which the Greeks exploited by settling colonies there, from the 7th century BC onwards.

Source: Richard Cavendish and Trevor Oswald Ling, Mythology: An Illustrated Encyclopedia (Rizzoli, 1980), 202.

Needless to say, this theory is particularly favored by Georgian archaeologists, who have done much to expose the maginificence of Colchis' archaeological heritage. However, the dates for their finds are somewhat too late to have influenced the Mycenaean myth of Jason. The main gold-yielding site, Vani, dates only from the eighth to sixth centuries BCE, a time when, as evidenced by Homer, the Jason myth was already being told in Greece.

Two non-metallic versions of this theory are that the wealth of Colchis was composed of sheep (see here for this theory), or that the golden wealth of Colchis was actually fields of grain. The latter theory was proposed by Adolf Faust in 1898 and was adopted by the Soviet Union as a way of emphasizing agriculture and instilling proletarian pride in twentieth-century Georgians, then under Soviet control. As one Soviet man reported to an American visitor in the 1940s:

It was to Colchis that Jason went to find the Golden Fleece, you remember. Historians now think that the Golden Fleece was really the golden wheat which grows so richly there.

Source: James P. Mitchell, Our Good Neighbors in Soviet Russia (New York: Noble and Noble, 1945), 149-150.

Two non-metallic versions of this theory are that the wealth of Colchis was composed of sheep (see here for this theory), or that the golden wealth of Colchis was actually fields of grain. The latter theory was proposed by Adolf Faust in 1898 and was adopted by the Soviet Union as a way of emphasizing agriculture and instilling proletarian pride in twentieth-century Georgians, then under Soviet control. As one Soviet man reported to an American visitor in the 1940s:

It was to Colchis that Jason went to find the Golden Fleece, you remember. Historians now think that the Golden Fleece was really the golden wheat which grows so richly there.

Source: James P. Mitchell, Our Good Neighbors in Soviet Russia (New York: Noble and Noble, 1945), 149-150.