LAKE TRITONIS

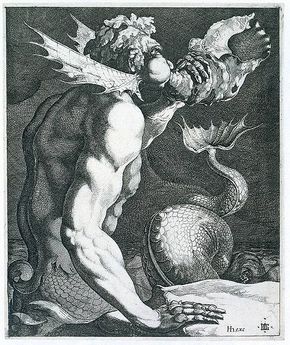

Triton, Jacob de Gheyn, c. 1615.

Edward Herbert Bunbury

A History of Ancient Geography among the Greeks and Romans (1879)

Major Rennell, in whose time the geography of this part of Africa was still very imperfectly known, was the first to suggest that the Lake Tritonis of Herodotus was in fact identical with the Lesser Syrtis of later writers, or rather comprised that and the inland lake of Lowdeah united (Geogr. of Herodot. p. 662): and this view is supported by Mr. Eawlinson, who speaks of the Lake Tritonis as "an inner sea" which stood to the Lesser Syrtis in the same relation as the Sea of Azof to the Euxine. (Eawlinson's Herodotus, vol. iii. p. 154, note 1.) But I confess I cannot see any necessity for its adoption. The terms in which Herodotus speaks of the Lake Tritonis and the tribes that dwelt around it are certainly such as to imply primd facie that it was a lake or inland piece of water: he nowhere alludes to its saltness, but calls it "a large lake" and represents it as the boundary between the nomad Libyans and the agricultural tribes. Even at the present day the salt lake known under the various names of Chott el Fejij, Chott el Melah, and Sebkah Faraoun (which is termed by Shaw Shibkah el Lowdeah), is not less than 110 miles in length: and there can be no doubt that at an earlier period it was much more extensive and was united with various other salt lakes in the same region, so as to cover an area of nearly double that extent, (See the description of the recent French travellers, M. Guenn in the Voyage Archeotogique dans la Re'gence de Tunis, vol. i. pp. 247-250; and M. Charles Martins in the Mevue des Deux Mondes for July, 1864.) It is at present separated from the 6ea only by a low sandy isthmus not more than ton miles in width, and there is every reason to believe that this is nothing more than a bar of sand gradually thrown up by tho action of the winds and tides. It is therefore not improbable that in the time of Herodotus, as well as in that of Scylax, it communicated with the sea by a narrow channel, or opening, which has gradually silted up.

Thus far the views of Major Rennell may be admitted to be wellfounded and to display his usual sagacity. But when he argues that because Herodotus describes Jason as driven by a storm "into the shoals of the Tritonian Lake " before he saw the land, he must therefore have supposed it to be a gulf of the sea, not an inland lake, and that that gulf could be no other than the Lesser Syrtis (p. 663); he certainly seems to be requiring an unreasonable amount of accuracy from a writer who is relating a mere poetical legend, and applying it to a country which he never visited. Supposing the name of the Lesser Syrtis to be still unknown to fame, "the shoals of the Tritonian Lake" would not be an unapt designation of the shallows which were in fact situated close to its mouth.

The mention by Herodotus (iv. 178) of "a large river," called the Triton, flowing into the Tritonian Lake, is a difficulty which admits of no satisfactory solution. No such river exists at the present day, nor could there ever have been any considerable perennial stream in that region of Africa. But Herodotus had evidently no idea of the real nature of the Tritonian Lake—a vast expanse of very shallow salt water, which was probably, even in his day, often dry in many places: he supposed it to bo a lake like any other, and that a lake of such extent should have a large river as its feeder was but a natural assumption. The same idea was as usual retained by later geographers, who ought to have been better acquainted with this part of Africa: Pliny (v. 4, § 28) speaks of a vast lake receiving the river Triton, from which it derives its name. Mela gives a precisely similar account (i. 7, § 36), and Ptolemy describes the river Triton as rising in the mountain of Vasaleton, and constituting three lakes, to one of which he gives the name of Tritonitis. The three lakes in question are probably only distinct names for three portions of the large expanse, which is sometimes united into one sheet of water, more often separated into three by dry intervals of sand covered with salt. (See the descriptions above cited.)

Scylax, who wrote only about a century after Herodotus, has left us (§ 110, p. 88, ed. Muller) a much more particular account of the lake Tritonis, as well as of the Lesser Syrtis, which he designates by that name, and describes as 2000 stadia in circumference, and much more dangerous and difficult of navigation than the other Syrtis. He then speaks of an island called Tritonis, which he places (apparently by a corruption of the text) in the Syrtis, and a river Triton. The lake (he adds) has a narrow mouth, in which there is an island, so that sometimes at low water there is no appearance of an entrance at all. The lake is of large extent, heing about 1000 stadia in circumference—a statement much below the truth. Here it is not quite clear whether the river Triton is the same with the narrow channel communicating with the sea, or not, though this is the most probable explanation. Ptolemy also distinctly speaks of the outflow of the river Triton into the sea, which he places ten miles to the west of Tacape, the modern Cabes (Ptol. iv. 3, § 11): and there can be no doubt that he here means the same river, which he elsewhere mentions as having its rise in the interior and flowing into the lake (lb. 3, § 19). Pliny and Mela add nothing whatever to our information.

The question is an interesting one, because it appears probable from recent geological researches that a great part of the Northern Sahara was at no very remote period covered by an inland sea, communicating with the Mediterranean at the Lesser Syrtis, and that it has been gradually elevated to its present level. Could we therefore prove that this communication was still open to some extent in the time of Herodotus, wo should be able to trace the last stage of this geological change by historical evidence. Unfortunately the testimony of Herodotus is very vague, and apparently derived from imperfect information; while that of Scylax, which is more complete and definite, is in some degree marred by a corruption of the text, which seems to arise from an accidental omission in our manuscripts. (See C. Muller ad loc.)

Source: Edward Herbert Bunbury, A History of Ancient Geography among the Greeks and Romans, vol. 1 (London: John Murray, 1879).

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons.