IOLCUS

(Iolkos)

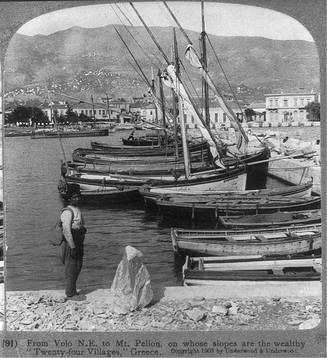

Volos in 1903, with Mt. Pelion. (Library of Congress)

Iolcus (or Iolkos) was Jason's hometown. In the late 20th century, archaeologists uncovered its remains at the site of Dimini near modern day Volos (Volo), which had long been suspected of being the ancient Argonaut's capital. The Dimini site includes Neolithic and Bronze Age occupation layers. After this description of Iolcus are the original reports from 1887 of the discovery of Mycenaean tholos tombs at Dimini, the first indication of the buried city still to be found.

From the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica:

VOLO, a town and seaport of Greece, on the east coast of Thessaly, at the head of the gulf to which it gives its name. Pop. (1907) 23,319. It is the chief seaport and second industrial town of Thessaly, connected by rail with the town of Larissa. The anchorage is safe, vessels loading and discharging by means of lighters. The port has a depth of 23 to 25 ft.

The Kastro, or citadel, of Volo stands on or close to the site of Pagasae, whence the gulf took the name of Sinus Pagasaeus or Pagasicus, and which was one of the oldest places of which mention occurs in the legendary history of Greece. From this port the Argonautic expedition was said to have sailed, and it was already a flourishing place under the tyrant Jason, who from the neighbouring Pherae ruled over all Thessaly. Two miles farther south stand the ruins of Demetrias, founded (290 B.C.) by Demetrius Poliorcetes, and for some time a favourite residence of the Macedonian kings. On the opposite side of the little inlet at the head of the gulf rises the hill of Episcopi, on which stood the ancient city of lolcus. At Dimini, about 3 m. W. of Volo, several tombs have been found which yielded remains of the later Mycenean Age.

From the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica:

VOLO, a town and seaport of Greece, on the east coast of Thessaly, at the head of the gulf to which it gives its name. Pop. (1907) 23,319. It is the chief seaport and second industrial town of Thessaly, connected by rail with the town of Larissa. The anchorage is safe, vessels loading and discharging by means of lighters. The port has a depth of 23 to 25 ft.

The Kastro, or citadel, of Volo stands on or close to the site of Pagasae, whence the gulf took the name of Sinus Pagasaeus or Pagasicus, and which was one of the oldest places of which mention occurs in the legendary history of Greece. From this port the Argonautic expedition was said to have sailed, and it was already a flourishing place under the tyrant Jason, who from the neighbouring Pherae ruled over all Thessaly. Two miles farther south stand the ruins of Demetrias, founded (290 B.C.) by Demetrius Poliorcetes, and for some time a favourite residence of the Macedonian kings. On the opposite side of the little inlet at the head of the gulf rises the hill of Episcopi, on which stood the ancient city of lolcus. At Dimini, about 3 m. W. of Volo, several tombs have been found which yielded remains of the later Mycenean Age.

DISCOVERY OF A THOLOS TOMB AT DIMINI, NEAR VOLO

As reported in the American Journal of Archaeology vol. III (1887), pp. 178 and 457, quoting other sources.

Volo (near).—Recent excavations at Dymenion, near Volo, have led to the discovery of a prehistoric tomb. The search began several weeks ago, when the Commissioner of the Archaeological Society of Athens proceeded to Dymenion to ascertain whether the antiquities thus found were authentic. Nothing official has yet been published, but it now appears certain that the tomb itself dates from the Homeric period. Most of the objects it contains are women's jewels in gold, but there are others in amber and in a kind of resin not yet defined. Almost all of them represent flowers or leaves. They are similar in artistic workmanship to those found in the tombs of Mykenai. Some of them are scarcely larger than a pin's head, and yet leave nothing to be desired in beauty and finish. The excavations of Dymenion, like those of Mykenai, tend to the supposition that the population was seafaring; and certain indications have led to the conclusion that the bodies deposited in the tomb of Dymenion were cremated.—N. Y. Evening Post, April 30.

Volo (near).--Domical Tomb at Dimenion or Dimini.—With regard to the early domical tomb, whose discovery was mentioned on p. 178, the following further particulars may be given. It resembles that of Menidi: the tholos is somewhat higher, measuring 9 met. with a diameter of 8.50 met. (instead of 8.35 at Menidi). The method of construction, with small stones superposed without mortar, is identical in both. The interior was filled in from above. The corridor or dromot, 13.30 met. long, was first cleared, and in it were found bones of men and animals, gold plaques, and fragments of vases of Mykenaian type. Similar remains were found in the tomb itself, but also several important objects, as follows: (1) gold objects; an engraved ring, two earrings (Schl., Mye., fig. 162), a tiny pitcher (cf. Menidi), pearls, shells, and spirals (cf. Menidi)., seven lilies, fourteen rosettes, many sheets of gold (cf. similar objects found at Menidi, Mykenai and Spata): (2) glass paste; sticks, shells, plaques, lily-form ornaments, rosettes, pearls, earrings, analogous to objects from Menidi and Spata: (3) bone; buttons, some with rosettes, square plaquette with 2 rosettes; cf. Menidi: (4) bronze objects; five arrow-heads and several rosettes: (5) stone; cone of black stone (cf. Schl., Tir. fig. 15), lapis-lazuli seal with figure, and two beads,—one of blue stone, the other of agate: (6) 20 conus shells (neolithic period), and fragments of vases sometimes with ornaments, sometimes simply with broad bands.--Revue Arch., July-Aug., 1887, pp. 79, 80.

As reported in the American Journal of Archaeology vol. III (1887), pp. 178 and 457, quoting other sources.

Volo (near).—Recent excavations at Dymenion, near Volo, have led to the discovery of a prehistoric tomb. The search began several weeks ago, when the Commissioner of the Archaeological Society of Athens proceeded to Dymenion to ascertain whether the antiquities thus found were authentic. Nothing official has yet been published, but it now appears certain that the tomb itself dates from the Homeric period. Most of the objects it contains are women's jewels in gold, but there are others in amber and in a kind of resin not yet defined. Almost all of them represent flowers or leaves. They are similar in artistic workmanship to those found in the tombs of Mykenai. Some of them are scarcely larger than a pin's head, and yet leave nothing to be desired in beauty and finish. The excavations of Dymenion, like those of Mykenai, tend to the supposition that the population was seafaring; and certain indications have led to the conclusion that the bodies deposited in the tomb of Dymenion were cremated.—N. Y. Evening Post, April 30.

Volo (near).--Domical Tomb at Dimenion or Dimini.—With regard to the early domical tomb, whose discovery was mentioned on p. 178, the following further particulars may be given. It resembles that of Menidi: the tholos is somewhat higher, measuring 9 met. with a diameter of 8.50 met. (instead of 8.35 at Menidi). The method of construction, with small stones superposed without mortar, is identical in both. The interior was filled in from above. The corridor or dromot, 13.30 met. long, was first cleared, and in it were found bones of men and animals, gold plaques, and fragments of vases of Mykenaian type. Similar remains were found in the tomb itself, but also several important objects, as follows: (1) gold objects; an engraved ring, two earrings (Schl., Mye., fig. 162), a tiny pitcher (cf. Menidi), pearls, shells, and spirals (cf. Menidi)., seven lilies, fourteen rosettes, many sheets of gold (cf. similar objects found at Menidi, Mykenai and Spata): (2) glass paste; sticks, shells, plaques, lily-form ornaments, rosettes, pearls, earrings, analogous to objects from Menidi and Spata: (3) bone; buttons, some with rosettes, square plaquette with 2 rosettes; cf. Menidi: (4) bronze objects; five arrow-heads and several rosettes: (5) stone; cone of black stone (cf. Schl., Tir. fig. 15), lapis-lazuli seal with figure, and two beads,—one of blue stone, the other of agate: (6) 20 conus shells (neolithic period), and fragments of vases sometimes with ornaments, sometimes simply with broad bands.--Revue Arch., July-Aug., 1887, pp. 79, 80.

DISCUSSION OF THE TOMBS OF DIMINI AND THE ARGONAUTS

From Georges Perrot and Charles Chipiez, History of Art in Primitive Greece, vol. 1: Mycenaean Art, trans. I. Gonino (London: Chapman and Hall, 1892), 429-432.

In concert with local tradition, we have attributed the great and quaint sepulchre of Orchomenos to the Minyans. Yet previous to reaching Boeotia, they had made some stay in Southern Thessaly. Here, by the tranquil waters of the Pagasetan Gulf, were learnt their first lessons in navigation, ere they ventured on those distant and adventurous expeditions, whose remembrance is preserved in the Argonaut myth. History knows them as the first settlers on that coast. Hence we shall not outstrip the bounds of probability by ascribing to these doughty and thrifty clans the oldest monuments which the district they once inhabited has preserved. The bee-hive tomb at Dimini, about four kilometres west of Volo, first drew the attention of students to that corner of the world. The village near which it stands lies by the sea, at the foot of the lower hills of Pelion, some little way from the conjectural site of ancient lolcos, a Minyan centre, whence Jason, with the heroes accompanying him, according to tradition, had started on his distant voyage. In the day of Strabo, however, the city had long lain in ruins. In the neighbourhood of a low hill called Tumba, terminating in a small plateau, are seen remains of a building known under the name of Laminospito, "haunted house"; where from the broken pottery of genuine Mycenian style which was found scattered about, Lolling, who visited the place in 1884, rightly inferred that they indicated the existence of an ancient sepulture. It was cleared two years later at the expense of the Greek government by MM. Lolling and Wolters. An account of their work, and of the objects collected in the course of the excavations in the chamber, has since been published. But as the building is so like the tomb at Menidi that it might almost pass for a replica of it, no ground-plan or section is given by us. Its main divisions are a trifle larger than those of the Menidian chamber: the entrance gate at Dimini is three metres sixty centimetres, and at Menidi three metres thirty centimetres. Again, the diameter of the circular chamber at Tumba measures eight metres fifty centimetres, and its fellow eight metres thirty-five centimetres. Both are extremely ill built. The roof at Dimini has long ago fallen in; but its height must have been nine metres. The circular slab which formerly covered the dome, one metre twelve centimetres in diameter and twelve centimetres in thickness, was discovered amidst the rubbish filling the chamber. This implies an arrangement which is met here for the first time; on the other hand, along the inner face of the stone beam over the doorway, we find the relieving triangular cavity. But the dromos, three metres thirty centimetres broad, owing to the steepness of the hill, is much shorter than at Menidi. The entrances both to the passage and the grave have been walled up with loose stones; but the blockage does not extend quite up to the lintel.

The dromos must have been filled in immediately after the interment. Layers of ashes and other burnt material are probably the result of sacrificial fires. Ashes also cover the floor of the chamber to a depth of five centimetres, and do not appear to be due to cremation rites, for human remains—a well-preserved skull and other bones—which have been found amongst the ashes, bear no trace of the action of fire.1 Here, too, have been picked up scraps of ornaments, described—for no drawings have been made of them—as bearing a close analogy to the similar objects from Mycenae, Nauplia, Menidi, and Spata, as well as from Peloponnesus and Central Greece. Gold is very scarce, and the ornaments made of it extremely small; but glass squares, pendants, and buttons abound; stone implements and marble beads, half-a-dozen bone buttons or so, were also discovered. The grave was doubtless rifled in antiquity; what we find are but scraps which, being small, eluded the vigilance of the thieves.

The fragmental pottery is certainly of Mycenian style, but utterly devoid of interest. On the other side of the gulf, hard by the site of Pagasu, another hypogaeum has been cleared by M. Wolters; this has yielded a whole series of vases, many of which have been sufficiently restored to enable us to recognize in them shapes and forms dear to the Mycenian potter at his best. The hill on whose slope the vaults are dotted about, rises sheer from the eastern side of the bay. The chambers are small, almost square, and twelve metres at the side, by one metre fifty centimetres in height; they are built of irregular schistose blocks, and larger slabs of this same stone make up the roof, the door-posts, and the lintel. The door, so far as may be judged, is narrower above than below, and was walled with dry stones. That they were covered over with earth is certain, else they would have been destroyed much sooner, and eased of their furniture, which they retained until lately. From one of these graves—excavated by an inhabitant of Volo—have come nearly all the vases filling the two plates which accompany M. Welter's paper. It looks as if other discoveries ought to be made in this necropolis. Strewing the ground are schistose blocks and slabs without number, the sole relics of many of these graves; some, however, may still be hidden under the sod. The whole country around shows traces of an industry that goes back to a remote period. Hard by Dimini, at a place called Palaeo-Kastro of Seskla, Dr. Lolling also picked up chips of pottery whose family likeness to the Mycenian vases is unmistakable. He would identify the spot with the Ormenion mentioned in the catalogue of ships. On the other hand, the idea, if ever entertained, of connecting the ruinous circular chamber situate between the twin summits of the citadel of Pharsales with a domed-grave, must be abandoned. It has neither a dromos, nor ever had a cupola: it is no more than an old cistern. The open gutter or channel which brought rain-water to the cistern appears along the rocky height overhanging the reservoir.

From Georges Perrot and Charles Chipiez, History of Art in Primitive Greece, vol. 1: Mycenaean Art, trans. I. Gonino (London: Chapman and Hall, 1892), 429-432.

In concert with local tradition, we have attributed the great and quaint sepulchre of Orchomenos to the Minyans. Yet previous to reaching Boeotia, they had made some stay in Southern Thessaly. Here, by the tranquil waters of the Pagasetan Gulf, were learnt their first lessons in navigation, ere they ventured on those distant and adventurous expeditions, whose remembrance is preserved in the Argonaut myth. History knows them as the first settlers on that coast. Hence we shall not outstrip the bounds of probability by ascribing to these doughty and thrifty clans the oldest monuments which the district they once inhabited has preserved. The bee-hive tomb at Dimini, about four kilometres west of Volo, first drew the attention of students to that corner of the world. The village near which it stands lies by the sea, at the foot of the lower hills of Pelion, some little way from the conjectural site of ancient lolcos, a Minyan centre, whence Jason, with the heroes accompanying him, according to tradition, had started on his distant voyage. In the day of Strabo, however, the city had long lain in ruins. In the neighbourhood of a low hill called Tumba, terminating in a small plateau, are seen remains of a building known under the name of Laminospito, "haunted house"; where from the broken pottery of genuine Mycenian style which was found scattered about, Lolling, who visited the place in 1884, rightly inferred that they indicated the existence of an ancient sepulture. It was cleared two years later at the expense of the Greek government by MM. Lolling and Wolters. An account of their work, and of the objects collected in the course of the excavations in the chamber, has since been published. But as the building is so like the tomb at Menidi that it might almost pass for a replica of it, no ground-plan or section is given by us. Its main divisions are a trifle larger than those of the Menidian chamber: the entrance gate at Dimini is three metres sixty centimetres, and at Menidi three metres thirty centimetres. Again, the diameter of the circular chamber at Tumba measures eight metres fifty centimetres, and its fellow eight metres thirty-five centimetres. Both are extremely ill built. The roof at Dimini has long ago fallen in; but its height must have been nine metres. The circular slab which formerly covered the dome, one metre twelve centimetres in diameter and twelve centimetres in thickness, was discovered amidst the rubbish filling the chamber. This implies an arrangement which is met here for the first time; on the other hand, along the inner face of the stone beam over the doorway, we find the relieving triangular cavity. But the dromos, three metres thirty centimetres broad, owing to the steepness of the hill, is much shorter than at Menidi. The entrances both to the passage and the grave have been walled up with loose stones; but the blockage does not extend quite up to the lintel.

The dromos must have been filled in immediately after the interment. Layers of ashes and other burnt material are probably the result of sacrificial fires. Ashes also cover the floor of the chamber to a depth of five centimetres, and do not appear to be due to cremation rites, for human remains—a well-preserved skull and other bones—which have been found amongst the ashes, bear no trace of the action of fire.1 Here, too, have been picked up scraps of ornaments, described—for no drawings have been made of them—as bearing a close analogy to the similar objects from Mycenae, Nauplia, Menidi, and Spata, as well as from Peloponnesus and Central Greece. Gold is very scarce, and the ornaments made of it extremely small; but glass squares, pendants, and buttons abound; stone implements and marble beads, half-a-dozen bone buttons or so, were also discovered. The grave was doubtless rifled in antiquity; what we find are but scraps which, being small, eluded the vigilance of the thieves.

The fragmental pottery is certainly of Mycenian style, but utterly devoid of interest. On the other side of the gulf, hard by the site of Pagasu, another hypogaeum has been cleared by M. Wolters; this has yielded a whole series of vases, many of which have been sufficiently restored to enable us to recognize in them shapes and forms dear to the Mycenian potter at his best. The hill on whose slope the vaults are dotted about, rises sheer from the eastern side of the bay. The chambers are small, almost square, and twelve metres at the side, by one metre fifty centimetres in height; they are built of irregular schistose blocks, and larger slabs of this same stone make up the roof, the door-posts, and the lintel. The door, so far as may be judged, is narrower above than below, and was walled with dry stones. That they were covered over with earth is certain, else they would have been destroyed much sooner, and eased of their furniture, which they retained until lately. From one of these graves—excavated by an inhabitant of Volo—have come nearly all the vases filling the two plates which accompany M. Welter's paper. It looks as if other discoveries ought to be made in this necropolis. Strewing the ground are schistose blocks and slabs without number, the sole relics of many of these graves; some, however, may still be hidden under the sod. The whole country around shows traces of an industry that goes back to a remote period. Hard by Dimini, at a place called Palaeo-Kastro of Seskla, Dr. Lolling also picked up chips of pottery whose family likeness to the Mycenian vases is unmistakable. He would identify the spot with the Ormenion mentioned in the catalogue of ships. On the other hand, the idea, if ever entertained, of connecting the ruinous circular chamber situate between the twin summits of the citadel of Pharsales with a domed-grave, must be abandoned. It has neither a dromos, nor ever had a cupola: it is no more than an old cistern. The open gutter or channel which brought rain-water to the cistern appears along the rocky height overhanging the reservoir.